Promoting a More Adaptable Physician Pipeline

In this paper, James Capretta argues that the current system for regulating the physician workforce is not flexible enough to ensure that enough doctors make it into the field to serve all patients. Mr. Capretta offers a number of reforms that, he argues, would streamline the educational and licensing processes for new and immigrating doctors.

Contributors

The views expressed are those of the author in his personal capacity and not in his official/professional capacity.

To cite this paper: James C. Capretta, “Promoting a More Adaptable Physician Pipeline”, released by the Regulatory Transparency Project of the Federalist Society, March 25, 2020 (https://rtp.fedsoc.org/wp-content/uploads/RTP-FDA-Health-Working-Group-Paper-Physician-Supply.pdf).

This paper is adapted from a report originally published by the American Enterprise Institute under the title “Policies affecting the number of physicians in the US and a framework for reform” (https://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Report-Policies-affecting-the-number-of-physicians-in-the-US-and-a-framework-for-reform.pdf)

Executive Summary

Since the latter half of the 19th century, the medical profession has been effectively regulating itself through state medical boards and control of the organizations that certify educational and training institutions. The federal government participates in (but does not directly control) residency programs through partial funding provided mainly by Medicare. Further, it writes the laws that regulate the influx of foreign graduates of international medical schools. The federal government should encourage a more adaptive and flexible pipeline of physicians entering the US market by: shifting away from the excessively hospital-centric orientation of current residency training by directing aid to the residents themselves; promoting certification processes with fewer ties to the economic interests of the profession; using market prices to inform Medicare fees; testing a six-year undergraduate-medical school curriculum; and easing entry into the U.S. of more well-trained foreign-born physicians.

Introduction

CON Physicians in the United States have incomes well in excess of what their peers earn in other advanced economies. For instance, in 2019, US physicians are expected to earn an average income of $313,000, compared to $163,000 for their counterparts in Germany and $108,000 in France.1

One factor might be the high cost of medical training in the US compared to other countries. Three-fourths of 2019 medical school graduates in the US had student loan debts, with a median debt level of $200,000.2 By contrast, in Germany, most newly-trained physicians have no debt from medical school because state governments pay for their tuition.3

In a fully unregulated medical services market, with low barriers to entry for practitioners, one would expect supply to adjust as necessary to meet demand and thus lead to pricing that both sides of each transaction find satisfactory. But the market for medical care in the US is anything but unregulated. Public policies that have the effect of restricting the available supply of physician services may be driving up consumer prices. A study from 2015 showed that pricing for many common physician procedures was 8–26 percent higher in markets with high levels of consolidation among physicians groups compared to markets with more numerous and independent practices.4

In the US and elsewhere, public policy must balance the need to establish high professional standards for physicians with the goal of making the care patients receive as inexpensive as possible. Given the high cost of physician services in the US, it is appropriate to consider whether current policies are striking the right balance.

I. A Top-Line Perspective

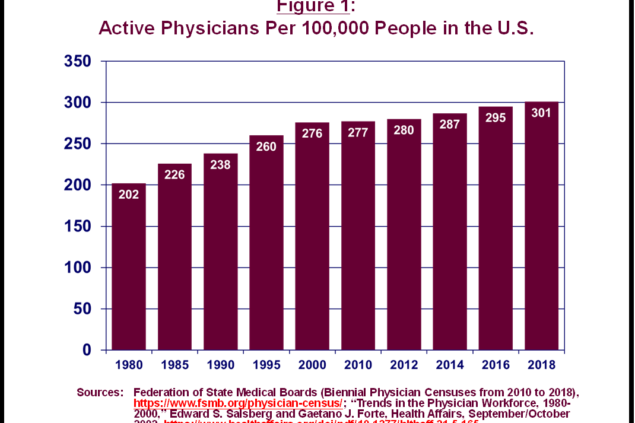

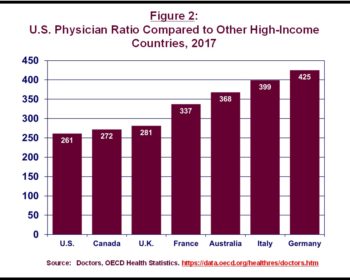

As shown in Figure 1, in recent decades, the US has experienced a steady increase in the ratio of physicians to the potential patient population. In 2018, there were 301 active physicians for every 100,000 residents, up nearly 50 percent since 1980. All other factors being equal, a higher ratio indicates more readily available services.

While the ratio has been rising in the US, it still falls below levels seen in other high-income countries. As shown in Figure 2, in 2017, the US had fewer active physicians relative to the size of its population than did Germany, Italy, Australia, France, the UK, and Canada.5

The American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC)—the association representing the interests of accredited medical schools and academic medical centers—has commissions periodic analyses of the adequancy of physician supply. Its latest forecast, from April 2019, projects rising demand, mainly from an aging and growing population, outpacing the growth in the physician workforce, such that there would be a shortfall of between 46,900 and 121,900 doctors in 2032.6 The AAMC uses this analysis to press for expanded federal financial support of residency training.

Projections of this kind are highly uncertain because of the many assumptions on which they are built. In 1997, there was growing concern in the physician community and among academic medical centers of an impending oversupply of doctors. The AAMC and its affiliated institutions recommended a cap on the number of residency slots funded by Medicare to slow the pipeline of physicians coming into the market.7 Congress obliged in the 1997 Balanced Budget Act. Now, the AAMC and other organizations are warning of an impending shortage and want Congress to remove the cap they helped put in place in the 1990s.

Ideally, the government should not be involved at all in trying to forecast and plan the size of the physician workforce. Rather, the overall structure that controls the physician pipeline should be flexible and adaptive enough to respond to signals of greater patient demand automatically. This analysis focuses on the existing system and whether it is sufficiently adaptable to changing market conditions.

Ideally, the government should not be involved at all in trying to forecast and plan the size of the physician workforce. Rather, the overall structure that controls the physician pipeline should be flexible and adaptive enough to respond to signals of greater patient demand automatically. This analysis focuses on the existing system and whether it is sufficiently adaptable to changing market conditions.

II. Historical Contex

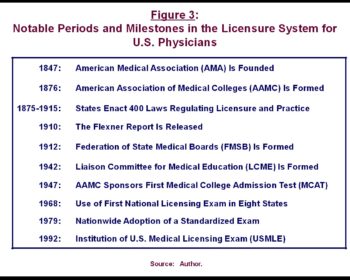

The current state-based system of medical licensure and medical school regulation can be traced to the organizational strength that mainstream physicians developed in the latter half of the 19th century. The American Medical Association (AMA) was formed in 1847 and its state affiliates immediately became powerful forces in state legislatures. (See Figure 3 for a list of historical milestones in the evolution of the physician licensure process.) In 1859, North Carolina established a state medical board for oversight of the profession, and in 1876, both California and Texas passed laws creating boards of examiners to issue licenses and examine the qualifications of persons claiming to be physicians. Over the period 1875–1915, state legislatures passed more than 400 separate laws governing medical practice, with increasing emphasis on licensure, competency exams, and oversight of the schools issuing medical degrees.8

A new and decisive phase began with a report funded by the Carnegie Foundation and written by Abraham Flexner in 1910.9 The Flexner report directed withering criticism at the for-profit school system and set a philosophical course for medical school curricula, clinical training, and physician licensure that has been the foundation for American medicine for more than a century.10

The enduring influence of Flexner’s study is threefold. First, it established that academic medical training in the US should be tied directly to scientific inquiry and evidence. Second, it placed academic medical centers, tied to the nation’s most prestigious universities, at the pinnacle of US health care. The nation’s top physicians naturally began gravitating to these institutions for their training and then stayed and practiced medicine at the growing network of facilities that developed around them. Third and crucially, Flexner’s findings became the predicate for a medical school and residency credentialing system that controls physicians’ entry into medical practice.

In the years after the report, states moved quickly to write licensing requirements that recognized only graduates of accredited medical schools, with the AMA (and, subsequently, additional bodies affiliated with the medical profession) establishing the certification criteria. From 1906 to 1944, the number of medical schools in the US producing newly-educated physicians fell from 162 to 69.11

In the years after the report, states moved quickly to write licensing requirements that recognized only graduates of accredited medical schools, with the AMA (and, subsequently, additional bodies affiliated with the medical profession) establishing the certification criteria. From 1906 to 1944, the number of medical schools in the US producing newly-educated physicians fell from 162 to 69.

III. Basic Framework for Physician Licensure in the US

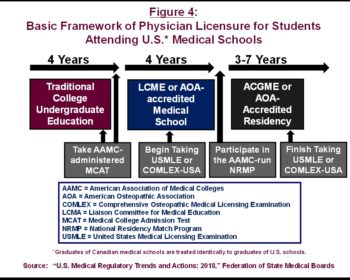

The traditional pathway to becoming a licensed physician involves multiple steps and takes many years to complete (See Figure 4). For most US residents, the starting point is admission to a qualified school. Admission to a medical school requires taking the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT), which is a standardized test developed and administered by the AAMC. Although there are exceptions, the typical path to a four-year medical school admission includes completion of a four-year undergraduate college education. Thus, it usually takes eight years of school-based education to obtain both an undergraduate and a medical degree.

Since 1942, the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) has established the criteria for accrediting the nation’s medical schools.12 The LCME is a joint enterprise of the AMA and the AAMC.13 The committee is comprised of 19 members: 15 MDs who either are in practice or serve as educators in medical schools, two current medical school students, and two nonphysicians. The AMA and AAMC nominate 14 of the 19 members, with the other five coming from candidates appointed by the LCME itself. Most states stipulate that conferring a medical license is predicated on graduation from an accredited institution. Further, graduation from an accredited school makes candidates eligible to take the standardized US Medical Licensing Exam, which is also a necessary step for licensure.14

States also require medical school graduates to enter into an approved residency training program, for a minimum of three years and perhaps seven or more depending on the specialization.15 In the fourth year of medical school, students participate in an elaborately structured residency assignment program that matches interested students with available residency slots. The students specify their preferences, and an algorithm matches them with residency programs in a manner that is supposed to maximize overall student and residency program satisfaction.16

Residency program accreditation began in 1972 with the establishment of the Liaison Committee for Graduate Medical Education, which transitioned into the American Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in 1981. The ACGME was founded by five sponsoring organizations: the American Board of Medical Specialties, the American Hospital Association, the AMA, the AAMC, and the Council of Medical Specialty Societies.

In recent years, the ACGME and the American Osteopathic Association (AOA) have jointly accredited the residency programs for allopathic and osteopathic physicians. Beginning with the academic year starting July 1, 2020, the ACGME will accredit residency training for both branches of medical school education. Consequently, the sponsoring organizations for the ACGME now also include the AOA and the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine.

Although states generally do not require further board certification by specialty societies as a condition of licensure, these certifications are increasingly important to the viability of physicians wishing to practice in the relevant specialties.17

In recent years, the ACGME and the American Osteopathic Association (AOA) have jointly accredited the residency programs for allopathic and osteopathic physicians. Beginning with the academic year starting July 1, 2020, the ACGME will accredit residency training for both branches of medical school education. Consequently, the sponsoring organizations for the ACGME now also include the AOA and the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine.

IV. Foreign-Born Physicians and International Medical Graduates

The US is heavily dependent on foreign-born physicians and on graduates (both US and foreign-born) of medical schools located outside the US and Canada.18 Currently, 29 percent of US-based physicians are foreign-born, including 22 percent who are foreign-born and remain non-US citizens even as they care for patients in every corner of the country.19 Physicians attending non-US medical schools are particularly important to ensuring access to care in underserved areas and are more likely than are their US-educated counterparts to become primary care physicians.20

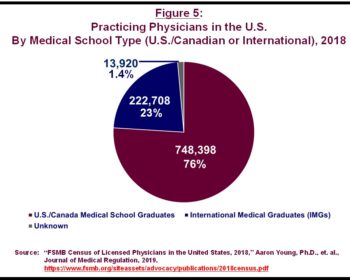

The typical pathway for non-US citizens to become practicing, US-based physicians is to attend medical school outside the US and Canada and then participate in a US-based residency program. Graduates of medical schools outside the US and Canada are known as international medical graduates (IMGs). As shown in Figure 5, in 2018, 23 percent of practicing US physicians are IMGs.

IMGs can be US citizens or foreign-born, non-US citizens. Many IMGs have attended schools in the Caribbean.

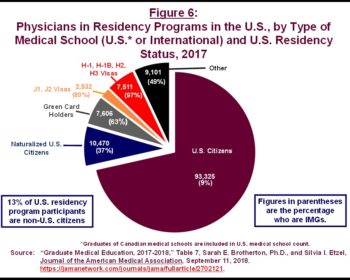

In 2017, of the more than 93,000 native US citizens who were participating in US-based residency programs, 9 percent were IMGs (Figure 6). There were also more than 10,000 foreign-born US citizens in these residency programs, of whom 37 percent were IMGs. More than 13 percent of residents were foreign-born, non-US citizens who were participating in these programs under various immigration authorities provided in federal law.

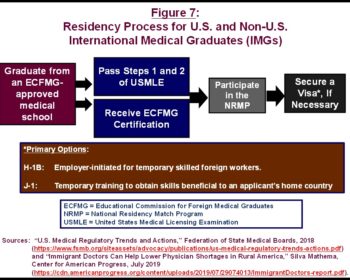

Figure 7 depicts the complex residency program and immigration law processes that foreign-born IMGs must navigate to obtain licenses from state medical boards. First, they must graduate from medical schools that have been certified by the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG), an organization created by the medical and teaching hospital community to oversee the qualifications of foreign-born physicians for practice in the US. ECFMG certification is a necessary condition for IMGs to enter US-based residency training.21

Foreign-born IMGs have essentially two paths to temporary legal status that will allow them to complete their residency requirements in the US.

Under the J-1 program, the ECFMG can sponsor candidates who would like to attend a US-based residency program with the stated intention of returning to their home country for at least two years after finishing their clinical training. Upon fulfillment of their two-year commitment, they can then apply for an alternative visa status that might allow them to return to work in the US as a practicing physician.22

J-1 visa holders have the option to apply for a Conrad 30 waiver, which would allow them to skip the two-year commitment in their home countries. The Conrad 30 waiver program was created to allow qualified IMGs to provide care in areas of the US with insufficient access to physician services, particularly rural areas. States sponsor the IMGs under the program and are allowed to award a maximum of 30 waivers per year.23 Participants in the waiver program must commit to serving at least three years at a health care facility in an underserved area, after which they can apply for a new residency status, either temporary or permanent.24

The other option for IMGs wishing to conduct their training in a US-based residency program is the H-1B visa program, which is aimed at bringing to the US foreign-born workers with specialized employment skills. Employers sponsor applicants, who must enter a lottery for one of the available annual visas, which are capped by law. However, higher education institutions, nonprofit organizations affiliated with exempt higher education institutions, and nonprofit and governmental research organizations are exempt from the H-1B cap.25 These exemptions allow many IMGs to obtain visas for their residency training, as the institutions are generally affiliated with universities. Nonetheless, after finishing their residency rotations, foreign-born IMGs must reenter the H-1B lottery to secure a visa that will allow them to work for a sponsoring employer.26

There are far more IMGs interested in attending US-based residency programs than there are available residency slots. As of July 2014, 9,326 IMGs were eligible but not yet assigned to a residency program through the National Residency Match Program.27

Employers sponsor applicants, who must enter a lottery for one of the available annual visas, which are capped by law. However, higher education institutions, nonprofit organizations affiliated with exempt higher education institutions, and nonprofit and governmental research organizations are exempt from the H-1B cap.25 These exemptions allow many IMGs to obtain visas for their residency training, as the institutions are generally affiliated with universities. Nonetheless, after finishing their residency rotations, foreign-born IMGs must reenter the H-1B lottery to secure a visa that will allow them to work for a sponsoring employer.

V. Public Subsidies and Policies for Graduate Medical Education

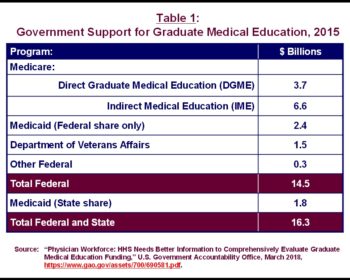

Whatever influence the federal government has over the pipeline of physicians is tied to its support for residency training—called graduate medical education (GME)—provided mainly through Medicare, Medicaid, and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). As shown in Table 1, in 2015 (the last year for which data are available), total federal spending on GME was $14.5 billion, according to the Government Accountability Office (GAO). Total federal and state support for GME, which includes the state share of Medicaid GME spending, was $16.3 billion.28

Medicare’s GME provisions provide, by far, the largest amount of support to institutions engaged in residency training. When Medicare was enacted in 1965, the key committees writing the initial legislation explicitly included payments for residency training in the program’s mandate, on the grounds that the institutions providing educational services to residents are, generally, some of the best facilities in the country, and Congress wanted Medicare beneficiaries to have access to them. Further, the law’s authors believed Medicare should shoulder its fair share of the costs of an educational system that has system-wide benefits.29

Federal policy has reinforced the essential role of accredited institutions by stipulating that GME funds can be paid only to institutions approved for residency training by either the ACGME or the AOA.30 Beyond this accreditation requirement, however, the federal government has taken a hands-off approach. Funding is provided with few demands for relevant data, to the point that several outside organizations have pointed to the paucity of information about program outcomes as a critical failure of current GME operations.31

With the prospective payment system, enacted in 1983, Medicare moved away from reimbursing facilities based on cost and instead calculated fixed-rate payments tied to the diagnoses of patients—the so-called diagnosis-related groups (DRGs). The new DRG payments were calculated to specifically exclude the costs associated with residency training.

To continue subsidizing the “bedside” education of physicians, Congress created two separate add-on funding streams for academic hospitals to run in tandem with the PPS. First, the program makes payments to institutions based on the direct costs of employing residents—called Direct Graduate Medical Education (DGME). This spending is supposed to offset expenses such as the salary stipends paid to residents, the salaries of the physicians supervising them, and associated overhead costs.32 Second, since 1983, Medicare also has paid hospitals for the indirect costs of running a residency program—the so-called indirect medical education (IME) subsidy.

Medicare makes DGME payments to facilities on a per-resident basis, using base year costs starting in October 1983 as a reference point. The base year amount is indexed to inflation. Medicare pays for an approved number of residents per hospital using a formula that incorporates the percentage of total patient days in the hospital that were attributed to Medicare beneficiaries.33

IME payments are supposed to address added costs that nonteaching facilities do not incur, such as the tests that residents may order. The IME payment is calculated as an add-on to the regular Medicare DRG rates, equal roughly to 5.5 percent of the base amount. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission estimates that the actual added, indirect costs of residency training is only 2.2 percent of teaching hospitals’ expenses. In 2015, paying hospitals an add-on of 2.2 percent, instead of 5.5 percent, would have saved $3.5 billion for the Medicare program.34

As noted previously, in 1997, at the urging of academic medical centers and the physician community, Congress capped the number of residency slots that are eligible for Medicare subsidization each year. Each hospital may apply for payments but only up to the number of residents on staff as of 1996. New training programs are exempt from a cap for five years, and the law allows for redistribution among facilities when residency slots go unused or when hospitals with residency programs cease operations.

Medicare’s payments to teaching facilities are significant on a per-resident basis. According to analysts at the Congressional Research Service, total Medicare DGME and IME payments in 2015 were $11.1 billion, for a resident census (on a full-time equivalent basis) of 85,700. Thus, on average, Medicare sent approximately $129,000 per resident per year to the nation’s teaching hospitals.35

In addition to Medicare, teaching hospitals in most states receive add-on payments from Medicaid. These payments are optional and fully at the discretion of state governments. They are also opaque and hard to track, as, historically, the federal government has collected little information from the states on GME costs and outcomes. The most useful information on Medicaid’s role in GME comes from organizations that have conducted ad hoc surveys of the states. According to the Government Accountability Office, 44 states provided some GME support to teaching hospitals in 2015, at a combined federal-state cost of $4.2 billion.36 This spending occurred with little federal oversight or accountability.

The VA directly supports training for 43,000 residents annually in its 1243 medical facilities. The purpose is to support the physician workforce generally throughout the country and specifically in the VA system. The average cost per resident was $139,000 in 2015—well above Medicare’s rate. The VA incurs costs directly with stipend payments to residents and incurs additional direct and indirect costs in a manner similar to non-VA facilities.37

Medicare’s payments to teaching facilities are significant on a per-resident basis. According to analysts at the Congressional Research Service, total Medicare DGME and IME payments in 2015 were $11.1 billion, for a resident census (on a full-time equivalent basis) of 85,700. Thus, on average, Medicare sent approximately $129,000 per resident per year to the nation’s teaching hospitals.

VI. More GME Funding Is Not the Answer

There has been an ongoing debate about the rationale and efficacy of public GME funding for more than two decades. In the 1990s, the AAMC and politicians representing the primary institutional recipients of public funding—including Sen. Pat Moynihan (D-NY) and Sen. Edward Kennedy (D-MA)—pushed for a new federal GME trust fund, financed with levies on all insurance plans. The argument was that ensuring a top-flight physician workforce, through educational and training requirements, was in the interest of all users of health care, not just enrollees in Medicare, and so therefore all participants in health insurance plans, public and private, should share in the burden of financing the costs of physician training. The trust fund idea was introduced as legislation and was featured in a report from the Institute of Medicine.38

The push for a publicly funded GME trust fund foundered, in part, because of disagreement regarding the underlying rationale for an active federal role in financing residency expenses. The national government does not provide comparable levels of support for the training costs of other high-skilled professions. Absent public subsidies, residency programs would continue; they provide value both to the physician candidates who improve their income prospects and to the institutions that employ them because they can charge for the services their residents provide to patients.

Economic theory would indicate that it is the residents, not the institutions that employ them, who incur the costs of their training, in the form of adjustments to the stipends they receive from the teaching hospitals where they work. Put another way, residents earn salaries equal to their net value to their employers, which is equal to the revenue they generate less the costs of their training.

Teaching hospitals might pay their residents somewhat more than their current net value if the training they provided were an investment producing a later return, in the form of even higher rates of billed services. But once physicians complete their residency requirements, they are under no obligation to remain working at the teaching facilities where they were trained. Because teaching hospitals are not guaranteed to capture the value of the training they provide, they pass on the full costs to the residents themselves.39

After Congress cut funding for both DGME and IME in the 1997 Balanced Budget Act, one might have expected resident salaries to fall, reflecting an increase in the net training cost to teaching hospitals. Instead, resident salaries continued to increase in the ensuing years. One possible explanation is that teaching hospitals treat government GME payments as general support funds untethered to the costs of their residency training programs. The general lack of auditable financial and programmatic data for GME spending supports this hypothesis.40

The AAMC and other advocates of the existing system of GME subsidies argue that public funding must increase to address the supposed physician shortage coming in 2032, and the 1997 cap on residency slots should be removed as well. But if the incidence of residency costs falls on the residents themselves, as the evidence suggests, and current GME funding does not factor directly into what residents are paid, then indiscriminate increases in Medicare GME payments will only subsidize the teaching institutions without altering the overall incentives that determine the number of residency slots.

The view that federal funding and aggregate residency enrollment is not strongly correlated also is supported by the trend in residency enrollment. Despite the cap imposed in federal law, the total number of residency slots at accredited institutions grew by 27 percent in the years after the cap went into effect.41 The new slots provide evidence that sponsoring residency training is financially beneficial to teaching hospitals, regardless of Medicare’s GME payments.

While it is difficult to justify increased GME funding to influence the overall numbers of physicians entering residency training, there is some justification for having separate DGME payments from Medicare to teaching hospitals, as a matter of fairness for the facilities. Medicare’s system of regulated payment rates does not allow hospitals to set the prices they charge for the services they provide to Medicare beneficiaries, which limits their ability to collect fees that fully take advantage of the services their residents provide to patients. Medicare DGME payments are a way to accommodate the diminished pricing flexibility hospitals have when financing the costs of residency training.42

The rationale for retaining current Medicare IME spending is on weaker ground. Numerous analyses have demonstrated that the current formula for paying institutions for the indirect, higher costs of care associated with residency training far exceeds their actual costs.

Teaching hospitals might pay their residents somewhat more than their current net value if the training they provided were an investment producing a later return, in the form of even higher rates of billed services. But once physicians complete their residency requirements, they are under no obligation to remain working at the teaching facilities where they were trained. Because teaching hospitals are not guaranteed to capture the value of the training they provide, they pass on the full costs to the residents themselves.

VII. The Role of the Medicare Fee Schedule

While government oversight and licensing requirements influence the supply of physicians in the US, so too does the expected income physician candidates can earn once they enter the profession. Prospective medical students must weigh the costs of securing an unrestricted physician license, measured both in direct out-of-pocket costs and time lost to earning a wage in an alternative profession, against the expected financial returns from practicing medicine.

This income side of the calculation is heavily influenced by government policy. In particular, the fees paid for individual physician services in Medicare are the most important factors in determining the earnings of the profession. The Medicare fee schedule (MFS)—the product of a long and complex legislative history—is used by not only the federal government to pay for physician services but also many private payers.

For the most part, private payers set higher fees than Medicare, but they often use the MFS as the starting point, sometimes by simply paying a multiple of what the MFS would pay for the same services. Private insurers find the MFS useful because it allows them to avoid negotiating prices for the thousands of codes physicians use to bill for their services. The federal imprimatur also gives it credibility.43

Originally, the MFS, which Congress created in 1989, was supposed to help steer higher levels of compensation toward physicians providing primary care and common services to patients, such as internists and family medicine practitioners. But the actual effect was the opposite. Specialists have boosted their incomes by performing more procedures; primary care physicians have less ability to adjust their incomes in this manner, as the bulk of their time is spent directly in communication with their patients.

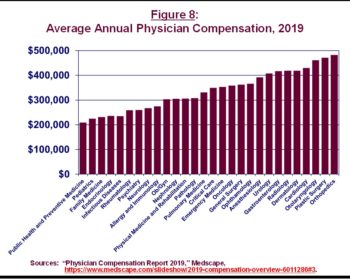

The disparities in earnings across physician specialties is stark. As shown in Figure 8, in 2019, family medicine physicians earned less than half of what orthopedic surgeons and cardiologists did.

The disparities in earnings across physician specialties is stark. As shown in Figure 8, in 2019, family medicine physicians earned less than half of what orthopedic surgeons and cardiologists did.

VIII. Toward a More Flexible and Adaptable Pipeline of Prospective Physicians

The ideal system of educating and training the future physician workforce would be flexible and adaptable enough to adjust automatically to changes in patient demand, without the need for agreement among federal or state policymakers on modifications to subsidy levels, available educational or training slots, or other regulatory requirements.

No system will be fully driven by unregulated market signals (due to the need for enforcing high standards on the profession). However, some reforms could make the physician pipeline more responsive to market requirements.44

A. Reform of Public GME Support.

The federal government’s financial support of GME should be modified not to cut overall costs but to address the major shortcomings of today’s payment methods.

First, Medicare, Medicaid, and VA funding for GME should be combined into one common funding stream. This will ensure that public subsidies are directed at meeting a single set of objectives, with clear goals and expected outcomes. Second, this funding should be adjusted to provide greater direct benefits to the residents themselves, in the form of vouchers or similar assistance, rather than the institutions employing them. Third, GME funds that support teaching institutions should be more flexible, to allow nonhospital institutions to compete for the funds. The current system encourages excessive reliance on hospital-based residency training even though most physician care now takes place in ambulatory settings.

B. Promotion of Medical Oversight with Fewer Ties to the Profession.

The federal government has the power to exert more leadership over the credentialing process through its large financing commitment to GME. Centralizing the entire process at the federal level, however, is not the answer, as the political pressures that created today’s system will not become less relevant with Congress writing the rules. Nonetheless, the federal government could use the leverage its funding provides to steer state governments toward a more balanced and neutral system of professional oversight. For instance, the federal government could stipulate that GME funds are to be sent only to institutions approved by a credentialing system that is more independent of persons or organizations with economic ties to the profession.

C. Development of a Market-Based MFS Based on Price Transparency Initiatives.

The Trump administration is committed to providing greater transparency on pricing to consumers. An effective price transparency effort also could provide the basis to introduce more market pricing into the MFS.

So far, the administration has focused its price transparency requirements on hospitals and their outpatient clinics. This agenda could be expanded to require physicians to disclose their prices for various services. The government should standardize what is being priced to allow consumers to make apples-to-apples comparisons, which will intensify competition and bring costs down. These disclosed prices could then be used to modify and adjust the MFS.

Adjusting the MFS in this way would bring stronger market signals to Medicare’s physician payment system, which in turn would influence the rates set by commercial insurers. As physician incomes adjust based on the competition that price transparency would bring, talented students considering a medical profession will get more market-driven signals regarding their likely earned incomes, which could help ensure the supply of services matches more closely with the services patients need.

D. Testing and Promotion of a Shorter Education Time Frame.

In total, it takes six years to earn the necessary degrees to become a licensed physician in Germany.

state governments finance medical education for students, and the process begins after completion of secondary school. There is a two-year, preclinical educational phase, focused on the basic scientific knowledge necessary for the profession. That is followed by four years of clinical training, more akin to the education received in US medical schools.45

The US has experimented with a shortened pathway to a medical degree, focused mainly on completion of medical school in three, rather than four, years. The government heavily promoted a three-year MD during World War II, to address the wartime physician shortage, and again in the 1970s, to lower costs. Since 2010, nine schools (less than 10 percent of the overall number) have been offering three-year medical degrees, mainly to candidates seeking to become primary care physicians.46

The federal government should encourage states and their medical oversight bodies to test a model of medical education that more closely follows the German approach of beginning just after high school.47 This would allow more coordination of a traditional undergraduate education with a medical school curriculum and perhaps open up the possibility of a six-year time frame for securing both degrees. Residency training would still be required, but the overall costs of becoming a licensed physician would fall, which would help with making the pipeline of physician candidates more flexible and responsive to other market signals.

E. Create a More Liberalized Pathway to H-1B Visas for Qualified Physicians and Physician Candidates.

Immigration policy has been highly contentious in the US for more than a decade, but policymakers agree more on the benefits of welcoming high-skilled workers than on other questions. The US has plenty of experience with a high percentage of physicians who were born and educated elsewhere, and yet the immigration laws still prohibit large numbers of qualified physician candidates from coming to the US.

Congress should amend current immigration law to either exempt physician candidates from the current H-1B cap altogether (beyond the exemption that already applies to certain organizations, including teaching hospitals attached to higher education institutions) or create a new, separate allocation for the physician profession to allow greater numbers of willing immigrants to come to the US and care for patients. This policy could be combined with incentives to encourage these immigrants to practice, at least for some minimum period of time, in areas that have limited access to physician services.

The federal government’s financial support of GME should be modified not to cut overall costs but to address the major shortcomings of today’s payment methods.

Conclusion

The current system of regulating the physician workforce, led by the states and centered on state medical boards, has produced satisfactory results, but it could be improved. The quality of care provided to patients is, for the most part, high, and medical care is continually improving. But the system is rigid and thus slow to adjust as needed to the changing demands of the patient population. And it may be restricting competition, which leads to higher prices.

The federal government, without usurping the role of the states, should provide stronger leadership over the process by using the funds provided for GME as a catalyst for reform. There should be more distance between the economic interests of existing practitioners and institutions and decision-making bodies that issue licenses to physician candidates. Further, the government should loosen its immigration laws to allow as many qualified and talented physicians who want to come to the US to do so, as there would be tangible benefits for the patients they would serve.

Footnotes

1 “How Much Are U.S. Doctors Paid? (Hint: A Lot More Than in the Rest of the World),” Advisory Board, September 24, 2019. https://www.advisory.com/daily-briefing/2019/09/24/international-physician-compensation.

2 “Medical Student Education: Debt, Costs, and Loan Repayment Fact Card,” AAMC (American Association of Medical Colleges), October 2019. https://store.aamc.org/downloadable/download/sample/sample_id/296/.

3 “A Comparison of Medical Education in Germany and the United States: From Applying to Medical School to the Beginnings of Residency.” Zavlin, Dmitry Zavlin, et al. 2017. German Medical Science (September). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC5617919/.

4 “Less Physician Practice Competition Is Associated with Higher Prices Paid for Common Procedures,” Daniel R. Austin and Laurence C. Baker, Health Affairs, 34, no. 10, October 2015. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0412.

5 The OECD 2017 data for the US do not match the data from the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB), possibly because the OECD’s definition of “active physician” excludes some doctors who are included in the FSMB total.

6 “The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2017 to 2032,” Tim Dall et al., IHS Markit Ltd., April 2019. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/c/2/31-2019_update_-_the_complexities_of_physician_supply_and_demand_-_projections_ from_2017-2032.pdf.

7 International Medical Graduates, the Physician Workforce, and GME Reform: Eleventh Report, Council on Graduate Medical Education, March 1998. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/advisory-committees/graduate-medical-edu/reports/archive/1998-March.pdf.

8 “The Early Development of Medical Licensing Laws in the United States, 1875–1900,” Ronald Hamowy, Journal of Libertarian Studies, 1979. https://cdn.mises.org/3_1_5_0.pdf.

9 Medical Education in the United States and Canada, Abraham Flexner, Carnegie Foundation, 1910. http://archive.carnegiefoundation. org/pdfs/elibrary/Carnegie_Flexner_Report.pdf.

10 “The Flexner Report—100 Years Later,” Thomas P. Duffy, Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 84 (September): 269–76, 2011. https:// www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3178858/pdf/yjbm_84_3_269.pdf.

11 “The A.M.A. and the Supply of Physicians,” Reuben A Kessel, Law and Contemporary Problems (Spring), 1970. https://scholarship. law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3288&context=lcp.

12 The LCME is the accrediting body for allopathic medical schools conferring medical doctor (MD) degrees. Schools for osteopathic medicine, which confer doctor of osteopathy (DO) degrees, are accredited by the American Osteopathic Association Commission on Osteopathic College Accreditation. The curricula for MD and DO degrees are similar. The two branches of the medical profession have their roots in different traditions, with allopathic training focused on laboratory-based diagnoses and osteopathy focused on holistic and primary care. These distinctions have become less meaningful over time as views among adherents of the two branches—and their approaches to educating and training physician candidates—have converged.

13 “Origin of the LCME, the AMA-AAMC Partnership for Accreditation,” Donald G. Kassebaum, Academic Medicine (February): 85–87, 1992. https://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/abstract/1992/02000/origin_of_the_lcme,_the_aamc_ama_partnership_ for.5.aspx.

14 U.S. Medical Regulatory Trends and Actions: 2018, FSMB (Federation of State Medical Boards), 2018b. https://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/publications/us-medical-regulatory-trends-actions.pdf.

15 Ibid.

16 “The Origins, History, and Design of the Resident Match,” Alvin E. Roth, Journal of the American Medical Association, 289, no. 7 (February 19): 909–12, 2003. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/195998.

17 Graduate Medical Education That Meets the Nation’s Health Needs, Jill Eden, Donald Berwick, and Gail Wilensky, ed., Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, 2014. https://www.nap.edu/read/18754/chapter/1.

18 Uniform accreditation standards for US and Canadian medical schools began with the Flexner report in 1910. Since 1942, the LCME has accredited Canadian medical schools. Graduates of Canadian schools have been treated identically to graduates of US medical schools for purposes of the residency matching program and licensure requirements. Today, the LCME accreditation process for medical schools in Canada is run in coordination with the Committee on Accreditation of Canadian Medical Schools (CACMS). In 2014, an agreement between the LCME and CACMS allowed the CACMS to establish standards applicable to Canadian schools. Disagreements over accreditation decisions by the LCME and CACMS are resolved by a joint review committee. Graduates of Canadian schools are not included in US counts of IMGs. See “Made-in-Canada Accreditation Coming for Medical Schools,” Barbara Sibbald, Canadian Medical Association Journal, 186, no. 2 (February), 2014. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3903760/.Sibbald (2014).

19 “U.S. Relies Heavily on Foreign-Born Healthcare Workers,” Lisa Rapaport, Reuters, December 4, 2018. https://www.reuters.com/ article/us-health-professions-us-noncitizens/u-s-relies-heavily-on-foreign-born-healthcare-workers-idUSKBN1O32FR.

20 “International Medical Graduates in the US Physician Workforce,” Padmini D. Ranasinghe, Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 115 (April): 236–41, 2015. https://jaoa.org/article.aspx?articleid=2213422.

21 Ibid.

22 “Immigrant Doctors Can Help Lower Physician Shortages in Rural America,” Silva Mathema, Center for American Progress, July 2019. https://cdn.americanprogress.org/content/uploads/2019/07/29074013/ImmigrantDoctors-report.pdf.

23 Ibid.

24 “Conrad 30 Waiver Program,” US Citizenship and Immigration Services, 2014. https://www.uscis.gov/working-united-states/students-and-exchange-visitors/conrad-30-waiver-program.

25 Ibid.

26 Mathema, 2019.

27 Ranasinghe, 2015.

28 “Physician Workforce: HHS Needs Better Information to Comprehensively Evaluate Graduate Medical Education Funding,” GAO (Government Accountability Office), March 2018. https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/690581.pdf.

29 “Social Security Amendments of 1965,” US House of Representatives, March1965. https://www.ssa.gov/history/pdf/Downey%20PDFs/Social%20Security%20Amendments%20of%201965%20Vol%201.pdf.

30 Medicare also provides educational support for dental and podiatric training in institutions accredited by the relevant oversight bodies. “Medicare Graduate Medical Education Payments: An Overview,” Marco A. Villagrana, Congressional Research Service, February 2019. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/IF10960.pdf.

31 Eden, Berwick, and Wilensky, ed., 2014.

32 “Federal Support for Graduate Medical Education: An Overview,” Elayne J. Heisler et al., Congressional Research Service. December 27, 2018. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44376.pdf.

33 Ibid.

34 “Graduate Medical Education Payments,” Mark Miller, Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, February 20, 2015. https://www. nhpf.org/uploads/Handouts/Miller-slides_02-20-15.pdf.

35 Heisler, et al., 2018.

36 GAO, 2018.

37 Heisler, et al., 2018.

38 On Implementing a National Graduate Medical Education Trust Fund, Institute of Medicine, 1997. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/5771/ on-implementing-a-national-graduate-medical-education-trust-fund.

39 “The Economics of Graduate Medical Education,” Amitabh Chandra, Dhurv Khullar, and Gail R. Wilensky, New England Journal of Medicine, 370 (June): 2357–60, June 2014. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1402468.

40 Ibid.

41 Heisler, et al., 2018.

42 Medicare Hospital Subsidies: Money in Search of a Purpose, Sean Nicholson, Washington, DC: AEI Press, 2002. https://www.aei.org/ wp-content/uploads/2011/10/20040218_book168.pdf.

43 “In the Shadow of a Giant: Medicare’s Influence on Private Physician Payments,” Jeffrey Clemens and Joshua D. Gottlieb, Journal of Political Economy, 125, no. 1 (February): 1–39, 2017. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdfplus/10.1086/689772.

44 Many other analysts and expert bodies have made recommendations to improve the system of educating and training physicians. The recommendations in this report echo some of the concepts found in this earlier work. In particular, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission has made numerous sensible recommendations for reform over many years, and the 2014 report from the Institute of Medicine included a comprehensive set of recommendations that are similar in their overall direction to what is proposed here. See Aligning Incentives in Medicare. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, June 2010, http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/ reports/Jun10_EntireReport.pdf; and Eden, Berwick, and Wilensky, ed., 2014.

45 “A Comparison of Medical Education in Germany and the United States: From Applying to Medical School to the Beginnings of Residency,” Dmitry Zavlin, et al., German Medical Science, September 2017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC5617919/.

46 “Comprehensive History of 3-Year and Accelerated Medical School Programs: A Century in Review,” Christine C. Schwartz, et al., Medical Education Online, 23, no. 1, December 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30376794.

47 “Why America Faces a Doctor Shortage,” Tim Rice, City Journal. Septemer 26, 2018. https://www.city-journal.org/why-america-faces-doctor-shortage-16194.html.