Pay Data Collection

In this paper, Diana Furchtgott-Roth and Gregory Jacob discuss the EEOC’s 2016 rule requiring employers to disclose their employees’ compensation data to the federal government in order to minimize the “pay gap”, and argue that this data collection is destined to prove fruitless, will lead the EEOC away from stamping out actual wage discrimination, and saddle the economy with costly paperwork and red tape.

Contributors

Diana Furchtgott-Roth

Gregory Jacob

This paper was the work of multiple authors. No assumption should be made that any or all of the views expressed are held by any individual author. In addition, the views expressed are those of the authors in their personal capacities and not in their official/professional capacities.

To cite this paper: D. Furchtgott-Roth, et al., “Pay Data Collection”, released by the Regulatory Transparency Project of the Federalist Society, September 4, 2017 (https://rtp.fedsoc.org/wp-content/uploads/RTP-Labor-Employment-Working-Group-Paper-Pay-Data-Collection.pdf).

Executive Summary

2016 Bud Light Advertisement1

Amy Schumer: Bud Light Party here to discuss equal pay.

Seth Rogen: Women don’t get paid as much as men and that is wrong.

Schumer: And we have to pay more for the same stuff.

Rogen: What?

Schumer: Yeah, cars.

Rogen: What?

Schumer: Dry cleaning.

Rogen: What?

Schumer: Shampoo.

Rogen: What? You pay more but get paid less? That is double wrong. I’m calling everyone I know, and I’m telling them about this. This has got to stop.

Schumer: Bud Light proudly supports equal pay. That’s why Bud Light costs the same no matter if you’re a dude or a lady.

2017 Audi Advertisement2

Male narrator: What do I tell my daughter?

Do I tell her that her grandpa’s worth more than her grandma?

That her dad is worth more than her mom?

Do I tell her that despite her education, her drive, her skills, her intelligence, she will automatically be valued as less than every man she ever meets?

Or maybe, I’ll be able to tell her something different.

On screen: Audi of America is committed to equal pay for equal work. Progress is for everyone.

Women don’t get paid as much as men.” “Do I tell [my daughter] that her grandpa’s worth more than her grandma; that her dad is worth more than her mom?” You’ve probably heard it before — perhaps also as, “Women earn 77 cents for every dollar earned by men” — the so-called “pay gap” or “wage gap.” On one level, it’s a relatively simple statistic. The “gender pay gap” is the comparison of the overall average earnings of working women to working men. For example, in 1979, women made, on average, $182 per week; men, $292; for an overall female-to-male earnings ratio of 62.3 percent (“Women earned 62 cents to every dollar earned by men.”).3 Today, women earn around $719 per week; men, $871; for a ratio of 82.5 percent (“Women earn 83 cents on the dollar compared to men.”).4 The math may be simple — and the Bud Light and Audi ads certainly make it sound straightforward — but around this “pay gap” has formed a now decades-old policy debate essentially over two questions: what causes the overall earnings difference, and what should be done about it?

This paper is about one federal agency’s flawed attempt to do something about it — the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the nation’s employment discrimination watchdog,5 issued a rule in 2016 requiring employers to disclose their employee’s compensation data to the federal government.6 By the end of March 2018, employers with 100 or more employees will be required to have collected, organized on forms, and reported to the EEOC a summary of their employees’ pay.7

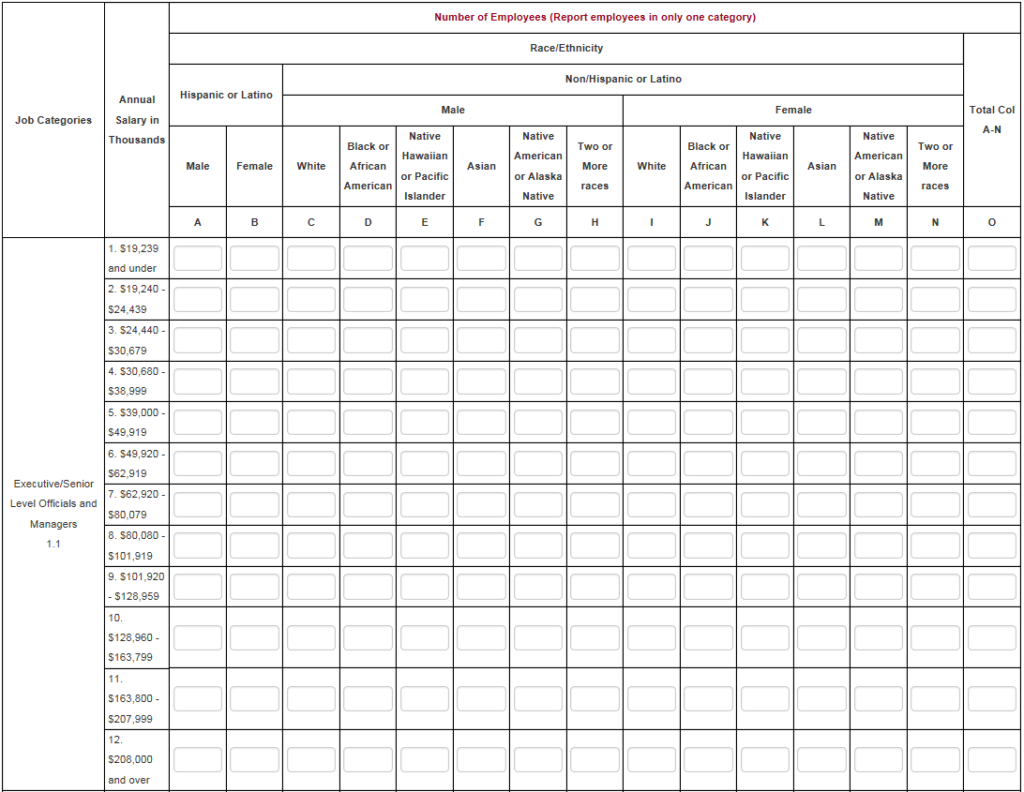

To collect it, the EEOC vastly expanded one of its longstanding reports, the Employer Information Report or “EEO-1,”8 which was previously a single matrix that reported employees in ten broad job categories, and by demographic information (sex, race, and ethnicity).9 Now, the EEO-1 has become a collection of three forms, totaling 21 matrices and 3,660 data entry cells, reporting employees by job category, demographics, pay data (in the form of “W-2 income” organized by “pay bands”), and, another new data point, employee’s hours worked.10 It’s best illustrated by example — below is one of the new matrices for the “Executive/Senior Level Officials and Managers” job category.

The EEOC primarily hopes to use this reporting to ferret out pay discrimination. A worthy cause. The data, however, is destined to prove fruitless — and worse, it will lead the EEOC away from stamping out actual wage discrimination, as evidenced by the federal government’s previous attempt to collect pay data. All the while, the new EEO-1 report will further saddle the economy with costly paperwork and red tape, ultimately harming the American workers the EEOC claims to be protecting.

I. Up and Down the Regulatory Seesaw

The federal government has been here before. The push to collect private employers’ pay data took off sometime in the 1990s; perhaps most notably, in 1997, with the introduction of the first version of the so-called “Paycheck Fairness Act” in Congress.11 A politically polarizing piece of legislation,12 the Paycheck Fairness Act would make several drastic alterations to the Equal Pay Act,13 the federal statute making law “equal pay for equal work” between women and men.14 Most important for our purposes, one of the bill’s provisions from the start and for the past 20 years: a requirement that the EEOC issue a regulation to collect employers’ compensation data.15

Coinciding with introduction of the Paycheck Fairness Act in 1997, the U.S. Labor Department’s Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP) launched an effort, and in November 2000 issued a final rule, called the “Equal Opportunity Survey” (EO Survey), to collect pay data from companies that do business with the federal government (federal contractors).16 (OFCCP enforces employment nondiscrimination and affirmative action rules applicable to federal contractors only, separate and apart from the EEOC.17) The EO Survey collected compensation and demographic information similar to the new EEO-1 report, though OFCCP’s survey also collected information on recent “personnel activity” (hiring, promotion, and termination data) and employees’ job tenure (years of service).18

Under the George W. Bush administration, OFCCP immediately began questioning the utility of the data. A 2005 study by the research firm Abt Associates, originally commissioned by OFCCP in 2002, confirmed the suspicion.19 Not only did Abt find the EO Survey useless, it was also counterproductive — the survey “would be expected to produce large numbers of ‘false positives.’”20 In other words, the “predictive analytics” derived from the survey would tend to point OFCCP and its enforcement resources toward federal contractors without pay issues — the proverbial wild goose chase.

OFCCP rescinded the survey in 2006, concluding:

[T]he EO Survey has no utility to OFCCP or to contractors. In fact, valuable enforcement resources are misdirected through the use of the EO Survey. Further, the lack of utility of the EO Survey, the contractors’ burden of completing the EO Survey, and the burden to OFCCP to collect and process EO Survey data that will yield such a poor targeting system are too significant to justify its continued use.21

Two years later, pay data collection was on the way back. As a Senator, former President Obama supported the Paycheck Fairness Act,22 as well as the even more expansive Fair Pay Act,23 both of which would require federal agencies to collect pay data. As a presidential candidate in 2008, he pushed the “pay gap” on the campaign trail,24 and “closing the pay gap” was a significant plank of the Obama administration.25 It was much touted, for example, that the “first law”26 President Obama signed was the “Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act” — a relatively narrow provision pertaining to the statute of limitations in certain pay discrimination cases.27 The Obama administration also had high hopes of signing into law the broader Paycheck Fairness Act, which had passed the U.S. House of Representatives in early 2009 alongside the Ledbetter bill28 but eventually stalled in the Senate in late 2010.29

Back to early 2010: coinciding with the Senate’s initial push to take up the Paycheck Fairness Act, the Obama administration began revving the federal bureaucracy, creating a “White House National Equal Pay Enforcement Task Force” in January 2010.30 The task force’s chief objective was to coordinate government efforts to “crack down on violations of equal pay laws.”31 The task force also proposed a specific mission for the EEOC: “Collect data on the private workforce to better understand the scope of the pay gap and target enforcement efforts.”32

The agency delivered in the form of the new EEO-1 report. Via the “Paperwork Reduction Act” — a mechanism for the federal government to collect information from the public — the EEOC issued a draft data collection for public comment,33 and held a public hearing on it,34 in early 2016. In July, it submitted its final version to the White House’s Office of Management & Budget (OMB), which has sole control over the fate of public information collections under the Paperwork Reduction Act. OMB summarily approved the new EEO-1 report in late September 2016.35

[T]he EO Survey has no utility to OFCCP or to contractors. In fact, valuable enforcement resources are misdirected through the use of the EO Survey. Further, the lack of utility of the EO Survey, the contractors’ burden of completing the EO Survey, and the burden to OFCCP to collect and process EO Survey data that will yield such a poor targeting system are too significant to justify its continued use.

II. All Cost, No Benefit

It’s difficult to see how the EEOC’s new EEO-1 report avoids the fate of OFCCP’s EO Survey: all cost, no benefit. While well intended, the report would substantially increase employer data collection and reporting costs, while rendering the government less effective at identifying and combating actionable pay discrimination.

Consider first the cost-burden. The EEOC estimated that some 67,000 employers will annually file over 700,000 of the new EEO-1 reports,36 at a cost of over $50 million per year.37 This would encompass everything from personnel time and resources to generate and submit the form, to myriad implementation costs to train staff and update computer systems and software. EEOC’s views of the costs differed significantly from business groups’. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, for example, put it closer to $400 million annually — in pure labor costs alone.38 Regarding the “burden hours” to collect data and file the new report, the EEOC estimated it would take an employer, on average, a little over 30 hours.39 The Chamber of Commerce put the per-employer average closer to 130 hours.40

Estimates on both sides, to be sure, but the chief critique of the EEOC’s certainly rings true: the federal bureaucracy lacks the real-world experience to understand the amount of time and resources it takes to implement and integrate government regulation. Human resources and information technology staff, legal counsel, upper-level management and executives — all will variously be required to collect, enter, and verify the data. Technology “startup” expenses will also be significant, especially for smaller businesses, as costly outside consultants will be required to update systems and patch together human resources systems storing employee demographic data and compensation systems storing pay data. For larger, more complex organizations, consultants were already required to coordinate filing the old EEO-1, and those costs will only be greater with the new report. Quantifying these burdens on private businesses is foreign to an enforcement agency like the EEOC.

What of the countervailing benefit, then? The EEOC offered up no tangible, quantified gain. Rather, it submitted its hope the data will “enhance and increase the efficiency” and be “extremely useful in helping enforcement staff to investigate potential pay discrimination.”41 Namely, the agency plans to use the data for a “first assessment” of charges of discrimination, which may help with “planning an investigation.”42 The EEOC also hoped the collection process will facilitate “employer self-evaluation.”43 The agency plans to publicize aggregated EEO-1 data by industry and geographic region, which, “in conjunction with [employers’] preparation of the EEO-1 itself, may be useful tools for employers to engage in voluntary self-assessment of pay practices.”44

The EEOC’s hopes fall short at nearly every turn. Foremost, take the form’s broad job categories and pay bands, which are so open-ended to render the data useless for pay analysis. Employees in different positions and at different job levels will be bunched together as “Managers,” “Professionals,” “Sales Workers,” and so on.45 This is the crux of the “false positives” problem. The new EEO-1 report will misleadingly report pay disparities all over the place, as women and men, and employees of different races and ethnicities, will inevitably be unequally distributed in job categories and pay bands throughout a company. Employee distribution, however, is far different from the question of whether similarly-situated employees are paid the same. Job grade/level, tenure, education, experience, performance and productivity — these are the critical factors in pay decisions, the ones most inherently linked to compensation. Without them, pay disparities on the new EEO-1 report, which merely reflect employee distribution, will mean nothing. Worse, they will lead to baseless and costly investigations of employers, and to dead-end enforcement for the EEOC.

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) captured the issue neatly in a 2012 report titled “Collecting Compensation Data from Employers,” which was commissioned by the EEOC at the suggestion of the Obama administration’s National Equal Pay Enforcement Task Force.46 NAS broadly reviewed methods and means for “measuring and collecting pay information.”47 Of some interest to NAS was the EEOC’s EEO-4 report, which has, since the 1970s, required state and local governments to biennially report their employees by job category, demographics, and annual salary — similar to the new EEO-1 report.48 In preparing its report, NAS interviewed a high-ranking official at the Department of Justice, who had this to say about the EEO-4 report (the EEOC and the Justice Department share enforcement jurisdiction over state and local governments; thus, both access the EEO-4):

[D]emographic data collected on the EEO-4 reports are invaluable for enforcement purposes, but the wage data on the form are currently less useful. The job categories and the wage bands report on the EEO-4 form are too broad, and the current EEO-4 does not include any other information, such as longevity (years of service), which can be a key determinant of salary in the public sector. In order to allow meaningful analysis, the department needs salary information in narrower job classes and information about years of service in the job class.49

Also problematic is the EEOC’s decision to collect pay data in the form of “W-2 Income.” According to the agency, W-2 data is best because it “incorporates different kinds of supplemental pay” beyond, for example, annual salary.50 Indeed, W-2 Income includes some 22 different sources of compensation51 — the problem being, many of the sources are the legitimate result of employee performance or choice, such as tips, overtime pay, and fringe benefits. During the public input period, commenters strongly urged the EEOC to collect employees’ annualized “base pay,” which is the overwhelming bulk of employee compensation, as well as the form of pay most controlled by employers.52 NAS similarly urged the EEOC not to collect “actual earnings or pay bands,” but instead to collect “rates of pay,” which would “best illuminate earnings levels.”53 The EEOC went with more confusion, and in the end, W-2 Income will only inject into the data more “noise” — information that distracts from the true indicia of wage discrimination, and that will ultimately lead the EEOC to more “false positives.”54

What of the EEOC’s hopes to “facilitate employer self-evaluation?” Theoretically, some employers may use the collection process as a springboard to self-assess their pay (though many already do). But it’s hard to see how the aggregated data “tool” — providing “comparative” pay information by industry and geographic region — will be of any assistance. It’s discriminatory for an employer to pay its own employees differently because of sex or other protected characteristics. There is simply nothing illegal about paying less than the competition; again, so long as employees under the same roof are paid equitably. Moreover, industry categories are often so broad — construction, retail, accommodation and food services, etc. — that finding relevant, useful comparators is near impossible.55

A final concern is the ability of the EEOC to protect pay data. Employers treat compensation information as highly sensitive and confidential, especially as a matter of competitive advantage. The EEOC and its staff are subject to strict, statutory prohibitions against disclosing information collected by the agency.56 Not all federal agencies are, though — OFCCP, which will also have access to the new EEO-1, is subject to lesser standards under the Freedom of Information Act, which could require disclosure upon request.57 Further, in court, employers’ individual EEO-1 reports could be acquired and disclosed widely by ill-intentioned litigants.58

The NAS report accordingly strongly recommended that the EEOC “develop more sophisticated techniques for protecting data” and “consider implementing appropriate data protection techniques.”59 There is no evidence the agency did any of this.60

A. The Harmful Effects of the New EEO-1 Report

The failings of the EEOC’s pay data rule are damaging on several levels. For one, not only will it not work, the unreliability of the data and the “false positives” problem are destined to lead the agency away from pursuing actual wage discrimination. This paper takes seriously the perniciousness of paying employees differently because of sex, race, ethnicity, or other protected characteristics. Among its many damaging effects, the economic costs of wage discrimination can span a lifetime’s work, affecting, for example, subsequent raises and employment and compounding over time. Effective enforcement and elimination of wage discrimination is crucial.

To that end, collecting and analyzing useless and misleading pay data is counterproductive. The EEOC has long had a sizable “backlog” of charges of discrimination of all types and forms; it currently stands at over 73,000 charges.61 These are individuals who have come to the agency alleging bias by an employer, and they are, each of them, awaiting and expecting a full review, and an answer, which can take years. Many of these charges involve individuals who have lost their livelihood; some involve heinous instances of sexual or racial harassment. As an institution entrusted to serve the American people, the EEOC does not have the time or resources to waste on efforts that do not support its mission.

The impact of the cost to employers makes matters worse. That is, the burden of the new form will harm the American workers the EEOC purports to benefit. The time and resources required to comply with government regulations like the new EEO-1 report come from somewhere. Here, human resources and legal departments will need to expand if not in size, certainly in scope — to generate and file the new form, and to defend against baseless and costly EEOC pay investigations. This displaces time and resources best put to growing a business, investing in innovation, and even investing in employees directly, in the form of training and skills development.62 Government policy should be tailored to this kind of growth and investment — the drivers of more and better opportunities, and rising wages for all Americans. In contrast, government policy like the new EEO-1 grows legal compliance departments.

The EEOC misread the costs and benefits of its pay data collection rule. The inordinate burden on employers, as well as the debilitating effects to the EEOC’s own enforcement efforts, will harm the American workers the agency claims to be defending. This kind of policy is unwarranted in any economic climate. In the current climate, however, with wage growth sputtering and economic growth still fighting to fully rebound from the “Great Recession,” government policy like the new EEO-1 report is especially damaging.

We now turn to something else the agency misread — its justification for pursuing the pay data rule in the first place.

While well intended, the report would substantially increase employer data collection and reporting costs, while rendering the government less effective at identifying and combating actionable pay discrimination.

Receive more great content like this

III. A Policy Behind the Times

Front and center in this section are the “pay gap,” and “equal pay” or “pay equity” — the ideal and concept of “equal pay for equal work.” Namely, a breed of policy prescriptions on “equal pay” have long been premised on the view that wage discrimination, as perpetrated by employers, is a significant driver of the pay gap. Consider the proposed “Findings” of the Paycheck Fairness Act: “Many women continue to earn significantly lower pay than men for equal work,” and “[i]n many instances, the pay disparities can only be due to continued intentional discrimination or the lingering effects of past discrimination.”63 OFCCP’s proposal of the EO Survey in 2000 sounded similar: “Today working women earn just 76.5 cents on the dollar compared to men. Black women earn 64 cents on the dollar compared to White men, and Hispanic women earn only 55 cents. The pay disparity exists even after accounting for differences in jobs, education, and experience.”64 Nearly 20 years on, the EEOC made the same connection in justifying its pay data rule: “Persistent pay gaps continue to exist in the U.S. workforce correlated with sex, race, and ethnicity;” and “Workplace discrimination is an important contributing factor to those disparities.”65 But what do the statistics really show?

A. Wage Discrimination is Not Driving the Pay Gap

Start with the obvious: the overall average “pay gap” reflects the universe of all working women compared to all working men. Randomly pick one from each and you could end up comparing a highly-paid male senior analyst at Apple in California, on the one hand, to a female kindergarten teach in Raleigh on the other; or a renowned female professor at the University of Michigan to a male janitor at the University of Alabama; or the male senior partner at a law firm to one of the firm’s female first-year associates. And so on for all 150 million working Americans. In this way, the overall earnings difference is apples and oranges. Correctly understood, it reflects 150 million individuals making an exponentially greater number of choices about themselves and each other.

To be clear, sex-based “wage discrimination” does happen, and should be addressed when it does. The EEOC’s own data, however, shows that it is highly improper and indeed unscientific to equate the pay gap with systemic invidious discrimination. The agency typically receives 2,000-3,000 charges annually merely alleging “sex-based” wage discrimination — approximately three percent of the total number of charges received each year.66 A subset of those charges is filed under the Equal Pay Act, which, recall, prohibits unequal pay for equal work between women and men. In 2016, the EEOC preliminarily found “reasonable cause” to believe discrimination had occurred in five percent of the Equal Pay Act charges it processed (57 of 1,201 charges).67 Another 14 percent were resolved at the administrative, pre-litigation stage in some form of benefit to the charging parties (170 of 1,201 charges), resulting in $8 million in awards.68 That’s a little over two percent of the overall $348 million in pre-litigation settlements awarded to charging parties in 2016.69 (Keep in mind that these “administrative resolutions” are far from determinations of discrimination, but instead agreements between the parties to settle prior to costly and protracted litigation.)

In terms of enforcement in court, the EEOC has brought few Equal Pay Act lawsuits in recent years. Two cases were filed in federal court in 2016, seven in 2015, two in 2014, five in 2013, and two each in 2012, 2011, 2010, and 2009 — comprising one to two percent of the agency’s litigation workload.70 Historically, the EEOC has recovered very little in Equal Pay Act litigation.71

The Equal Pay Act is, of course, one of several laws the EEOC enforces that prohibits wage bias. Overall, the agency recently reported that since 2010, it has “received more than 32,000 charges of pay discrimination on the basis of sex, race, or ethnicity, and the agency has obtained over $184 million in monetary relief for victims of pay discrimination.”72 Comparatively, those 32,000 charges were about five percent of the overall 660,000-plus charges of discrimination received since 2010.73 And, the $184 million in pay-related awards — overwhelmingly administrative resolutions — was 6.5 percent of the overall $2.8 billion in monetary benefits recovered.74

Perhaps the best evidence of the prevalence of wage discrimination comes from OFCCP.75 That agency has broad authority to conduct comprehensive, top-to-bottom compliance audits of federal contractors’ employment practices. It conducts thousands of compliance evaluations each year. And, as part of a review, OFCCP collects and analyzes detailed employee pay data. In its most recent budget report to the White House, OFCCP noted that from January 2010 to September 2015, it “remed[ied] pay discrimination” because of sex or race, or both, in “more than 100” of its over 20,000 compliance evaluations — so, less than one percent of the time.76 And, recall, this timeframe coincided with the White House’s National Equal Pay Enforcement Task Force and the Obama administration’s concerted effort to “crack down on violations of equal pay laws.”77

Again, wage discrimination undoubtedly — and unfortunately — occurs. The government’s enforcement data, however — the EEOC’s and OFCCP’s own data — suggests it’s not prevalent. Research over the past 20 years suggests something similar: wage discrimination is not driving the “pay gap.”

The EEOC admitted as much. Indeed, in its final proposal of the pay data rule, the agency made the key point: the majority of the overall earnings difference between the sexes is automatically explained by the occupations women and men are most likely to hold, the industries in which they work, and the relative level of work experience between the two groups.78 “Men are more likely to work in blue collar jobs that are higher paying, including construction, production, or transportation,” the agency noted, “whereas women are more concentrated in lower paying professions, such as office and administrative support position.”79 And all of the available evidence suggests that this disparity is driven not by discriminatory barriers, but rather is primarily attributable to the work preferences of the job-seekers themselves.

An additional point the EEOC did not but should have made is the extent to which “work patterns” also explain earnings differences. For example, the independent U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) identified in a 2003 report that women tend to “work fewer hours per year,” “are less likely to work a full-time schedule,” and “leave the labor force for longer periods of time.”80 Similarly, a 2010 GAO report analyzed women in management across a number of sectors, and found that female managers tended, among other things, to be more likely to work part time.81 A 2009 report by CONSAD Research Corporation, prepared for the U.S. Labor Department, largely echoed GAO. CONSAD explained that “numerous factors [] contribute to the gender wage gap,” and those factors “relate to differences in the choices and behavior of women and men in balancing their work, personal, and family lives.”82 They include, most notably, “the occupations and industries in which they work, and their human capital development, work experience, career interruptions, and motherhood.”83

These factors explain the vast majority of the overall earnings difference between the sexes. The research also consistently shows that there is a much smaller, “unexplained” portion of the difference — an amount that cannot be accounted for when analyzing available data. It’s at this point that the EEOC made an all-too-common logical leap. According to the agency, because there is this unexplained portion of earnings differences,84 thus, “discrimination — intentional or unintentional, systematic or at the individual level” necessarily “plays a role in explaining the gap,”85 and so revisions to the EEO-1 report to collection compensation data are “necessary” for the enforcement of the law.86 Note closely, here, that the EEOC’s justification for the pay data rule rests entirely on wage discrimination “playing a role” in the “pay gap,” while the EEOC has no idea how much of a role and can make no convincing case that the significant burdens imposed by the rule would actually do anything to address it.

The weight of the research over the past 20 years shows that measuring the impact of discrimination in earnings differences is at best problematic, and perhaps impossible. For example, regarding the “unexplained” portion of overall earnings differences, GAO’s 2003 report concluded: “It is difficult to measure and quantify individual decisions and possible discrimination”; and, “Because these factors are not readily measurable, interpreting any remaining earnings difference between men and women is problematic.”87 CONSAD put an even finer point on it: “[I]t is not possible now, and doubtless will never be possible, to determine reliably whether any portion of the observed gender wage gap is not attributable to factors that compensate women and men differently on socially acceptable bases, and hence can confidently be attributed to overt discrimination against women.”88

Harvard economist Claudia Goldin’s recent appearance on the Freakonomics podcast summed it up best. In response to a question about the role of employer bias in pay, Professor Goldin said:

It’s hard to find the smoking guns, OK? The smoking guns existed in the past. I have found many a smoking gun where you find actual evidence of firms saying, for example, “I do not hire Negroes.” Or, “I do not hire women.” I mean, you actually find these in 1939. We don’t find those smoking guns now, but what we do try to do is hold everything constant that we can hold, get the best data that we can get. And what remains we don’t call discrimination, we call wage discrimination. Discrimination is such a loaded word that we don’t want to use that, so we use quotes around “wage discrimination.” And so the first thing is, what type of data do you need to do that? It would be incredibly rich data. And a couple of people have put together data using administrative records that are phenomenally good data that can hold lots of things constant, that can track individuals over their lifetimes and get to the answer. And the answer is that it’s a pretty small number, this number for wage discrimination once you hold lots of things constant. It’s probably there, but we’re not quite certain whether these differences are due to the fact that women, even those without kids, have more responsibilities or take more responsibilities in their own families — taking care of their parents, for example. So the answer is that we don’t have tons of evidence that it’s true discrimination.89

In the face of all this, the EEOC decided to stick with the now decades-old line — wage discrimination simply must be an “important contributing factor” in the “pay gap.” To argue to the contrary is not to argue that wage discrimination does not exist. It does. The point is the EEOC’s pay data collection rule is not a rational response to the kind of discrimination we know to exist.

Moreover, in 2017, we know what drives the vast majority of earnings differences. Individuals’ career and work-life choices; educational opportunities and attainment; entry into higher-paying occupations and industries; historical tendencies and societal assumptions about work — these kinds of factors, applied across 150 million working Americans, explain why entire demographic groups make more, or less, than others. To be sure, many of these factors warrant policymakers’ consideration. However, as a policy response to the true causes of the “pay gap,” the new EEO-1 report is ultimately an irrelevant distraction.

Again, wage discrimination undoubtedly — and unfortunately — occurs. The government’s enforcement data, however — the EEOC’s and OFCCP’s own data — suggests it’s not prevalent. Research over the past 20 years suggests something similar: wage discrimination is not driving the “pay gap.”

Conclusion

It’s said, “Generals are always fighting the last war.” And so was the EEOC here. The agency, still working from an old regulatory to-do list, dusted off and pushed the tired idea of pay data collection at a time when we know so much more about the “pay gap,” and when “equal pay” is increasingly part of the public consciousness and trends in the private market. The final result: a regulation that will ultimately harm the American workers the EEOC claims to be protecting. The paperwork and compliance costs of the new EEO-1 report further shift resources and focus away from the type of economic activity — growth, innovation, investment — that could directly benefit Americans. On top of that, the unreliability of the data collected will shift the EEOC’s resources away from effective enforcement that actually remedies wage discrimination. Outdated, burdensome, ineffective: the EEOC’s new EEO-1 report is a waste for the American people.

Footnotes

1 See Seth Rogen and Amy Schumer talk about equal pay, YouTube (Sept. 15, 2016), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MdnjR45wBOQ

2 See Audi #DriveProgress Big Game Commercial: “Daughter,” YouTube (Feb. 1, 2017), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G6u10YPk_34

3 See U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Women in the labor force: a databook Table 16 (Dec. 2015), available at https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/womens-databook/archive/women-in-the-labor-force-a-databook-2015.pdf

4 See id.

5 U.S. Equal Emp’t Opportunity Comm’n, About EEOC, https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/

6 Proposed Changes to the EEO-1 to Collect Pay Data, Revised Proposal; 30-Day Notice, 81 Fed. Reg. 45,479 (July 14, 2016) [hereinafter EEO-1 30-Day Notice], available at https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2016-07-14/pdf/2016-16692.pdf; Notice of Office of Mgmt. and Budget Action, OMB CONTROL NUMBER: 3046-0007 (Sept. 29, 2016) [hereinafter OMB EEO-1 Approval], available at https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/DownloadNOA?requestID=275763

7 Federal contractors with 50-99 employees will continue to file the old EEO-1 report, which collects employees’ job category and demographic information only. See, e.g., EEO-1 30-Day Notice, supra note X, at 45,484.

8 The EEOC maintains a set of employer data collections called the “EEO Reports” — currently running are the EEO-1 (private employers), EEO-3 (local referral unions), EEO-4 (state and local governments), and EEO-5 (public schools) Reports. See generally U.S. Equal Emp’t Opportunity Comm’n, EEO Reports / Surveys, https://www.eeoc.gov/employers/reporting.cfm

9 The old EEO-1 report is available at: https://www.templateroller.com/template/2146806/form-sf100-employer-information-report-eeo-1.html

10 See U.S. Equal Emp’t Opportunity Comm’n, EEO-1 Survey, https://www.eeoc.gov/employers/eeo1survey/2016_new_survey.cfm

11 See Paycheck Fairness Act, S. 71, 105th Cong. (1997), available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/105th-congress/senate-bill/71; H.R. 2023, 105th Cong. (1997), available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/105th-congress/house-bill/2023

12 In the previous Congress, (2015-2016), 239 Members cosponsored the bill — 237 Democrats (the entirety of the Democratic caucus), one Independent, and one Republican; there was no meaningful action taken on it. See Paycheck Fairness Act, S. 862, 114th Cong. (2015), available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/862/cosponsors; H.R. 1619, 114th Cong. (2015), available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/1619/cosponsors

13 See Paycheck Fairness Act, S. 862, 114th Cong. (2015), available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/862; H.R. 1619, 114th Cong. (2015), available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/1619. See also, e.g., Access to Justice: Ensuring Equal Pay with the Paycheck Fairness Act: Hearing Before the Comm. on Health, Education, Labor & Pensions, 113th Cong. (2014), available at https://www.help.senate.gov/hearings/access-to-justice-ensuring-equal-pay-with-the-paycheck-fairness-act; A Fair Share For All: Pay Equity in the New American Workplace: Hearing Before the Comm. on Health, Education, Labor & Pensions, 111th Cong. (2010), available at https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-111shrg75805/html/CHRG-111shrg75805.htm; Jody Feder & Benjamin Collins, Pay Equity: Legislative and Legal Developments, Congressional Research Serv. (May 20, 2016), available at https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL31867.pdf

14 29 U.S.C. § 206(d), available at https://www.eeoc.gov/laws/statutes/epa.cfm

15 See Paycheck Fairness Act, S. 71, 105th Cong. (1997), available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/105th-congress/senate-bill/71; H.R. 2023, 105th Cong. (1997), available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/105th-congress/house-bill/2023. The most recent version of the Paycheck Fairness Act, introduced in the current Congress, still contains a provision requiring the EEOC to issue pay data collection regulations. See Paycheck Fairness Act, S. 819, 115th Cong. (2017), available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/819/text; H.R. 1869, 115th Cong. (2017), available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/819/text

16 See Government Contractors, Affirmative Action Requirements, 65 Fed. Reg. 68,022 (Nov. 13, 2000) [hereinafter EO Survey]. See also Linda Levine, The Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs and the Equal Opportunity Survey, Congressional Research Service (Sept. 14, 2006), available at http://www.mit.edu/afs.new/sipb/contrib/wikileaks-crs/wikileaks-crs-reports/RS20897.pdf

17 U.S. Dep’t of Labor, Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs, About OFCCP, https://www.dol.gov/ofccp/aboutof.html

18 See EO Survey, supra note X, at 68,047-48. A copy of the EO Survey is available at http://dciconsult.com/PDFs/EOSurvey.pdf

19 See Abt Associates, Inc., An Evaluation of OFCCP’s Equal Opportunity Survey (Summer 2005) (on file with author).

20 Id. at 38.

21 Affirmative Action and Nondiscrimination Obligations of Contractors and Subcontractors; Equal Opportunity Survey, 71 Fed. Reg. 53,023, 53,041 (Sept. 8, 2006), available at https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2006-09-08/pdf/E6-14922.pdf. OFCCP instead shifted its resources to increased “awareness,” issuing guidance to federal contractors on how to self-evaluate compensation practices and on the agency’s standards for investigation wage discrimination. See Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs; Voluntary Guidelines for Self-Evaluation of Compensation Practices for Compliance With Nondiscrimination Requirements of Executive Order 11246 With Respect to Systemic Compensation Discrimination, 71 Fed. Reg. 35,114 (June 16, 2006), available at https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2006-06-16/pdf/06-5457.pdf.; Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs; Interpreting Nondiscrimination Requirements of Executive Order 11246 With Respect to Systemic Compensation Discrimination; Notice, 71 Fed. Reg. 35,124 (June 16, 2006), available at https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2006-06-16/pdf/06-5458.pdf

22 See Paycheck Fairness Act, S. 766, 110th Cong. (2007), available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/110th-congress/senate-bill/766

23 See Fair Pay Act, S. 1087, 110th Cong. (2007), available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/110th-congress/senate-bill/1087. For a discussion of the Fair Pay Act, see Pay Equity: Legislative and Legal Developments, supra note X, at 8-9.

24 See, e.g., McCain calls for $300 million prize for better car battery, CNN.com (June 24, 2008), http://www.cnn.com/2008/POLITICS/06/23/campaign.wrap/

25 See, e.g., Closing the Pay Gap: It Starts with a Conversation (April 8, 2014), https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/share/closing-pay-gap-starts-with-conversation

26 See Obama for America TV Ad: “First Law,” YouTube (June 21, 2012), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ayILjfYs7xw

27 Pub. L. No. 111-2 (Jan. 29, 2009), available at https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ2/pdf/PLAW-111publ2.pdf. The Ledbetter Act overturned its namesake, the 2007 Supreme Court case Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 550 U.S. 618 (2007), available at https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/06pdf/05-1074.pdf

28 See H.R. 12, 111th Cong. (2009), available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th-congress/house-bill/12/all-actions

29 See S. 3772, 111th Cong. (2009), available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th-congress/senate-bill/3772/all-actions

30 See The White House, National Equal Pay Enforcement Task Force (Jan. 2010) [hereinafter Equal Pay Task Force], available at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/rss_viewer/equal_pay_task_force.pdf

31 Id. at 1.

32 Id. at 5.

33 Agency Information Collection Activities: Revision of the Employer Information Report (EEO-1) and Comment Request, 81 Fed. Reg 5,113 (Feb. 1, 2016) [hereinafter EEO-1 60-Day Notice], available at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/02/01/2016-01544/agency-information-collection-activities-revision-of-the-employer-information-report-eeo-1-and

34 See Public Input into the Proposed Revisions to the EEO-1 Report: Hearing Before the U.S. Equal Emp’t Opportunity Comm’n (Mar. 16, 2016) [hereinafter EEO-1 Hearing], https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/meetings/3-16-16/index.cfm

35 See OMB EEO-1 Approval, supra note X. In 2014, in response to a White House directive, OFCCP issued its own proposal to collect federal contractors’ compensation data. See Government Contractors, Requirement to Report Summary Data on Employee Compensation, U.S. Dep’t of Labor, Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs, 79 Fed. Reg. 45,562 (Aug. 8, 2014), available at https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2014-08-08/pdf/2014-18557.pdf; Office of the Press Secretary, The White House, Presidential Memorandum – Advance Pay Equality Through Compensation Data Collection (April 8, 2014), available at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2014/04/08/presidential-memorandum-advancing-pay-equality-through-compensation-data. However, according to the EEOC’s initial, February 2016 draft revised EEO-1, “OFCCP plans to utilize EEO-1 pay data for federal contractors with 100 or more employees instead of implementing a separate compensation data survey as outlined in its August 8, 2014, NPRM.” See EEO-1 60-Day Notice, supra note X, at n.23.

36 The number of reports is greater than the number of employers because companies with multiple physical locations (“establishments”) are required to file multiple reports. See 30-Day Notice, supra note X, at n.44.

37 See id. at 45,493.

38 U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Agency Information Collection Activities; Notice of Submission for OMB Review, Final Comment Request: Revision of the Employer Information Report 2 (Aug. 15, 2016) [hereinafter Chamber of Commerce EEO-1 30-Day Notice Comments], available at https://www.uschamber.com/sites/default/files/documents/files/uscc_eeo1_comments_omb_august_15.pdf

39 See EEO-1 30-Day Notice, supra note X, at 45,496.

40 See, e.g., Chamber of Commerce EEO-1 30-Day Notice Comments, supra note X, at 20.

41 See EEO-1 30-Day Notice, supra note X, at 45,483.

42 See U.S. Equal Emp’t Opportunity Comm’n, Small Business Fact Sheet: The Revised EEO-1 and Summary Pay Data, https://www.eeoc.gov/employers/eeo1survey/2017survey-fact-sheet.cfm

43 See EEO-1 30-Day Notice, supra note X, at 45,480.

44 Id. at 45,491.

45 The ten job categories are (1) Executive/Senior Level Officials and Managers; (2) First/Mid-Level Officials and Managers; (3) Professionals; (4) Technicians; (5) Sales Workers; (6) Administrative Support Workers; (7) Craft Workers; (8) Operatives; (9) Laborers and Helpers; and (10) Service Workers.

46 See National Research Council, National Academy of Sciences, Collecting Compensation Data from Employers (2012) [hereinafter NAS Report], available at https://www.nap.edu/catalog/13496/collecting-compensation-data-from-employers

47 Id. at 1.

48 See U.S. Equal Emp’t Opportunity Comm’n, 2015 EEO-4 Survey, https://egov.eeoc.gov/eeo4/

49 See NAS Report, supra note X, at 20 (presentation by Jocelyn Samuels, senior counselor to the Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights (May 24, 2011)).

50 See EEO-1 30-Day Notice, supra note X, at 45,486.

51 See id. at n.50.

52 See EEO-1 Hearing, supra note X, at Written Testimony of David S. Fortney, Esq.

53 See NAS Report, supra note X, at 4.

54 Business groups raised a similar issue regarding the EEOC’s manner of collecting employees’ “hours worked.” Hours worked by “hourly” employees can be accurately reported — employers track it. However, to collect hours worked by “salaried” employees, which employers largely do not track, the EEOC directed employers to enter a “proxy” estimate of 40 hours for full-time employees and 20 hours for part-time. See 30-Day Notice, supra note X, at 45,488. This means that in many job categories, accurate information on hourly employees will be combined with inaccurate information on salaried employees, which only further undermines the integrity of the data.

55 See U.S. Equal Emp’t Opportunity Comm’n, Job Patterns For Minorities And Women In Private Industry (EEO-1), https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/employment/jobpat-eeo1/

56 See 42 U.S.C. 2000e-8(e). See also EEO-1 30-Day Notice, supra note X, at 45,491-92.

57 See EEO-1 30-Day Notice, supra note X, at 45,492.

58 The risk of public disclosure by way of cyber-attacks is also all too real. The EEOC’s new rule came a year out from the 2015 data breach at the Office of Personnel Management, which compromised the private personal data of over 20 million individuals. See, e.g., Office of Personnel Mgmt., Cybersecurity Resource Ctr., What Happened, https://www.opm.gov/cybersecurity/cybersecurity-incidents/

59 See NAS Report, supra note X, at 5.

60 See EEO-1 30-Day Notice, supra note X, at 45,491-92 (Sec. X. Confidentiality of EEO-1 Data).

61 U.S. Equal Emp’t Opportunity Comm’n, Performance and Accountability Report 12 (Nov. 15, 2016), https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/plan/upload/2016par.pdf

62 The new EEO-1 report is also an impediment to growth in a very specific sense — expanding from the 99th to the 100th employee has now become costlier.

63 See S. 862, 114th Cong. (2015), available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/862

64 Government Contractors; Affirmative Action Requirements, 65 Fed. Reg. 26,088 (May 4, 2000), available at https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2000-05-04/html/00-10991.htm

65 See EEO-1 30-Day Notice, supra note X, at 45,481.

66 See U.S. Equal Emp’t Opportunity Comm’n, Enforcement & Litigation Statistics, Bases by Issue, https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/bases_by_issue.cfm

67 See U.S. Equal Emp’t Opportunity Comm’n, Enforcement & Litigation Statistics, Equal Pay Act Charges (Charges filed with EEOC), https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/epa.cfm. The data is collected by the government’s “fiscal year” (October 1 – September 31).

68 See id.

69 U.S. Equal Emp’t Opportunity Comm’n, All Statutes (Charges filed with EEOC) FY 1997 – FY 2016, https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/all.cfm

70 U.S. Equal Emp’t Opportunity Comm’n, EEOC Litigation Statistics, FY 1997 through FY 2016, https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/litigation.cfm

71 See id.

72 U.S. Equal Emp’t Opportunity Comm’n, EEOC’s Progress Report: Advancing Equal Opportunity for All (Jan. 19, 2017), https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/plan/2017progress.cfm

73 U.S. Equal Emp’t Opportunity Comm’n, Enforcement & Litigation Statistics, Equal Pay Act Charges, https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/all.cfm

74 See U.S. Equal Emp’t Opportunity Comm’n, Enforcement & Litigation Statistics, All Statutes (Charges filed with EEOC), https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/all.cfm.; U.S. Equal Emp’t Opportunity Comm’n, Enforcement & Litigation Statistics, EEOC Litigation Statistics, FY 1997 through FY 2016, https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/litigation.cfm

75 U.S. Dep’t of Labor, Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs, About OFCCP, https://www.dol.gov/ofccp/aboutof.html

76 See U.S. Dep’t of Labor, Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs, FY 2017 Congressional Budget Justification, available at https://www.dol.gov/sites/default/files/documents/general/budget/CBJ-2017-V2-10.pdf; U.S. Dep’t of Labor, Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs, FY 2016 Congressional Budget Justification, available at https://www.dol.gov/sites/default/files/documents/general/budget/2016/CBJ-2016-V2-10.pdf; U.S. Dep’t of Labor, Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs, FY 2015 Congressional Budget Justification, available at https://www.dol.gov/dol/budget/2015/PDF/CBJ-2015-V2-10.pdf; U.S. Dep’t of Labor, Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs, FY 2014 Congressional Budget Justification, available at https://www.dol.gov/dol/budget/2014/PDF/CBJ-2014-V2-10.pdf; U.S. Dep’t of Labor, Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs, FY 2013 Congressional Budget Justification, available at https://www.dol.gov/dol/budget/2013/PDF/CBJ-2013-V2-10.pdf; U.S. Dep’t of Labor, Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs, FY 2012 Congressional Budget Justification, available at https://www.dol.gov/dol/budget/2012/PDF/CBJ-2012-V2-04.pdf

77 See Equal Pay Task Force, supra note X.

78 See EEO-1 30-Day Notice, supra note X, at 45,482 (citing Francine Blau & Lawrence Kahn, The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations, Institute for the Study of Labor 73, Table 4 (Jan. 2016), available at http://ftp.iza.org/dp9656.pdf).

79 See id.

80 U.S. General Accounting Office, Women’s Earnings: Work Patterns Partially Explain Difference Between Men’s and Women’s Earnings 10-11 (Oct. 31, 2003) [hereinafter Women’s Earnings], available at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-04-35

81 U.S. Government Accountability Office, Women in Management: Analysis of Female Managers’ Representation, Characteristics, and Pay 8-21 (Sept. 20, 2010), available at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-10-892R

82 CONSAD Research Corporation, An Analysis of the Reasons for the Disparity in Wages Between Men and Women 15 (Jan. 12, 2009) [hereinafter CONSAD Report], available at https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/public-policy/hr-public-policy-issues/documents/gender%20wage%20gap%20final%20report.pdf (Note: the link to CONSAD’s report on its website is no longer operational, and the U.S. Department of Labor does not link to the report.).

83 Id.

84 See EEO-1 30-Day Notice, supra note X, at 45,482 (“Most of the remaining 35.4% of the gender gap cannot be explained by differences in education, experience, industry, or occupation.”).

85 See id. at 45,482 (citing Francine Blau & Lawrence Kahn, The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations, Institute for the Study of Labor 73, Table 4 (Jan. 2016), available at http://ftp.iza.org/dp9656.pdf).

86 See id. at 45,481.

87 See Women’s Earnings, supra note X, at 17. GAO reports in 2010 and 2011 found the same, noting the extreme difficulties in explaining the entirety of earnings differences, and making clear that their analyses did not or could not determine the role of discrimination in pay differences. See U.S. Government Accountability Office, Women in Management: Analysis of Female Managers’ Representation, Characteristics, and Pay 8-21 (Sept. 20, 2010), available at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-10-892R; U.S. Government Accountability Office, Gender Pay Differences: Progress Made, but Women Remain Overrepresented among Low-Wage Workers 5 (Oct. 12, 2011), available at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-12-10

88 See CONSAD Report, supra note X, at 35.

89 Freakonomics Radio, The True Story of the Gender Pay Gap (Jan. 7, 2016), http://freakonomics.com/podcast/the-true-story-of-the-gender-pay-gap-a-new-freakonomics-radio-podcast/