Occupational Licensing Run Wild

The authors of this paper provide a historical analysis of occupational licensure in the United States, discuss the costs and benefits of our licensing system, explore so-called “licensing creep,” and propose solutions to help address “occupational licensing run wild.”

Contributors

Dana Berliner

Daniel Greenberg

Paul J. Larkin, Jr.

Clark Neily

Ryan Nunn

Jonathan Riches

Luke A. Wake

This paper was the work of multiple authors. No assumption should be made that any or all of the views expressed are held by any individual author. In addition, the views expressed are those of the authors in their personal capacities and not in their official/professional capacities.

To cite this paper: D. Berliner, et. al., “Occupational Licensing Run Wild”, released by the Regulatory Transparency Project of the Federalist Society, November 7, 2017 (https://rtp.fedsoc.org/wp-content/uploads/RTP-State-Local-Working-Group-Paper-Occupational-Licensing.pdf).

Executive Summary

Occupational licensure has grown completely out of control in the United States; its misuse and overuse dampens job creation, innovation, productivity, and consumer choice. We refer to the tendency to impose unjustifiable, arbitrary, and protectionist licensing requirements as “occupational licensing run wild.” Our paper demonstrates the scope of the problem, explains the many costs that excessive occupational licensure creates, and describes the emerging bipartisan consensus in favor of reform and rollback of state-level licensing regimes.

In recent decades, the scope of occupational licensure has increased significantly. In the 1950s, just one in twenty American workers needed government permission to do their jobs in the form of an occupational license. Today, at least 25 percent of the American workforce is subject to occupational licensing. Our paper begins by providing a brief history of occupational licensure and then explores competing explanations for its continuing expansion: is the expansion explained better by a “public interest/market failure” theory of benevolent regulators or by a “public choice” theory of self-interested special interest groups that have captured policymakers? We find that the latter explanation — public choice — better fits the facts.

The evidence in favor of the public choice account includes the wide variance in the occupations that are licensed across states — as well as the wide variance of licensing requirements in different states for the same occupations. If these laws benefited the public, we would expect something close to a nationwide consensus on what occupations are licensed, as well as consistency in the particular licensing requirements those occupations face. Instead, we see large interstate variation: even when there is nearly universal consensus across the states that some particular occupation should be licensed, the qualifications needed for licensure vary widely. The variance that is observed when only a relatively small number of states impose any licensing requirements, but those requirements are relatively onerous, seems even more difficult to square with a public interest explanation.

We next discuss what we call “licensing creep,” the tendency of those who work in regulated occupations to capture the agencies overseeing them and then lobby for the expansion of the agencies’ regulatory scope to include tangentially related occupations. This phenomenon continues to expand the problem of excessive licensure and its attendant costs.

Indeed, a growing body of research suggests that excessive occupational licensure creates large costs that are not publicly appreciated, such as higher consumer prices, restricted employment, and dampened innovation. Notably, this research also suggests that the benefits that are promised by defenders of extensive occupational licensing — such as improvements in quality of services, health, and safety — are largely absent. We provide a brief summary of academic research in this area, as well as anecdotal accounts of the human costs that excessive occupational licensure creates.

Because of the harm that occupational licensure run wild causes, there is growing bipartisan and nonpartisan consensus for reform. Across the political and ideological spectrum, there is broad recognition that the current licensing system is bad for the country. While libertarians and conservatives have long criticized these laws for interfering in the market, liberals have become more skeptical of these laws — particularly in the wake of research that state licensing regimes disproportionally harm minorities, individuals with criminal records, military families, immigrants, and lower-income Americans. Instead of seeing licensing as a way to protect consumers, policymakers are learning that crowd-sourced technology gives consumers increasingly reliable information about the quality of those whom they might hire.

Next, we turn briefly to a problem closely related to excessive occupational licensure: certificate of need (“CON”) laws. These laws, a fixture in the medical and transportation fields, require government approval before one may enter certain markets. And they often allow existing businesses in those markets to object to and prevent new entrants. CON laws allegedly protect the public. But in practice, they, like occupational licensing run wild, create unnecessary barriers to entry while dampening innovation.

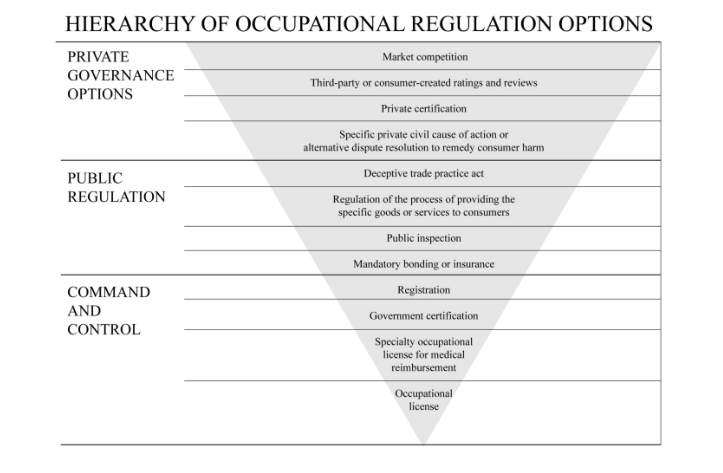

We close by offering several recommendations for reforming onerous occupational licensure. These include changing policymakers’ attitudes through education and illustration, going after the low-hanging fruit among existing regulations, and demonstrating the existence of effective alternatives to full-blown occupational licensure.

Solving the problem of occupational licensing run wild is no easy task, but given the growing and widespread recognition of the problems it presents, there is reason for optimism about reform.

I. A Brief History of Occupational Licensing in America

The impulse to regulate who may do what work is nothing new.1 Medieval guilds limited entry into various occupations, while the 13th and 14th centuries saw elementary forms of medical licensing in Germany, Naples, Sicily, and Spain.2 American Colonies saddled bakers, ferry services, innkeepers, lawyers, leather merchants, and peddlers with various forms of regulation,3 with full-blown occupational licensing making its appearance around the latter half of the 19th century, especially in the medical profession and allied fields.4

During that period, the Supreme Court confirmed the constitutionality of reasonable occupational licensing requirements. In Dent v. West Virginia, the Court considered a state law requirement that, to practice medicine, a physician must graduate from a reputable medical school and pass a qualifying examination or prove that he had practiced medicine in the state for ten years.5 The Court acknowledged that, because every individual has a right to pursue a lawful occupation, the legislature cannot arbitrarily prevent a person from working in the occupation of his choice.6 Nevertheless, the Court concluded that a state may adopt a physician licensing scheme as a means of protecting the public health and safety.7 Following its decision in Dent, the Supreme Court consistently upheld other regulations of health-related vocations8 and businesses,9 as well as licensing requirements imposed on a variety of other occupations as part of the state police power.10

The latter half of the 20th century saw an explosion in the number of occupations subject to a licensing requirement.11 Sixty years ago, the American economy rested on manufactured goods, and only 4-5 percent of the workforce was subject to a licensing requirement.12 But in today’s more service-oriented economy the number of licensed positions has skyrocketed. Since 1950, the percentage of the domestic workforce in positions subject to a licensing requirement has multiplied 500 percent and now stands at approximately 25 percent of the economy.13

Among the occupations subject to a licensing requirement are the following:

- Animal breeders

- Auctioneers

- Ballroom dance instructors

- Barbers

- Bartenders

- Cat groomers

- Cosmetologists

- Elevator operators

- Florists

- Fortune tellers

- Hair braiders

- Home entertainment installers

- Interior designers

- Makeup artists

- Manicurists and pedicurists

- Motion picture projectionists

- Plumbers

- Sheep dealers

- Taxi drivers

- Tour or travel guides

- Upholsterers

- Whitewater rafting guides

As these examples illustrate, occupational licensing’s reach is vast. Indeed, it is now one of the nation’s principal forms of economic regulation.

Sixty years ago, the American economy rested on manufactured goods, and only 4-5 percent of the workforce was subject to a licensing requirement.12 But in today’s more service-oriented economy the number of licensed positions has skyrocketed. Since 1950, the percentage of the domestic workforce in positions subject to a licensing requirement has multiplied 500 percent and now stands at approximately 25 percent of the economy.13

II. Occupational Licensing and Public Choice Theory

It is fair to ask why America, the self-styled “land of the free,” wound up regulating so many vocations and dropping so precipitously in global rankings of economic freedom, falling well behind Canada, Great Britain, and even formerly Soviet Georgia.14 Are American workers less skillful, conscientious, or responsible than their counterparts in other industrialized countries with lower rates of vocational licensing? Has there been an explosion of subspecialties within already licensed fields, with each new niche requiring a new and separate license? Or has there been a massive uptick in the number of injuries committed by incompetent or fraudulent practitioners?

No, no, and no. On the contrary, it turns out that the explanation for the explosion of occupational licensing schemes is more prosaic, more predictable, and less beneficial than the public might expect.

As discussed below, some — perhaps many — occupational licensing schemes are not public-spirited; instead, their sole function is to protect politically powerful incumbents from would-be competitors. Other licensing schemes, by contrast, even if misguided and ineffective, are plausibly motivated by a genuine desire to protect the public from unqualified or unscrupulous providers. Among the more plausible public-welfare rationales for occupational licensing, at least before the advent of the Internet and Smartphones, is what economists call “information asymmetry.” Consumers may be at a particular disadvantage in sectors that feature numerous providers of widely varying skills or quality, such as lawyers or taxi drivers, or when dealing with vocations where the “consumer” typically does not get to choose the provider, as with emergency medical technicians (EMTs).

The argument is that licensure can mitigate this lack of information and choice by ensuring that all practitioners possess some minimum level of training, education, or experience. In theory, this sets a floor below which no one may offer a potentially risky service and enables consumers to select from approved providers without needing to investigate their credentials or qualifications.15 Of course, suppliers will still vary in their qualifications above the minimum legal floor since a licensing process is not designed to eliminate suppliers with superior talents, only those with substandard skills. In theory, however, no unlicensed provider may operate, and no licensed provider will endanger the public due to inadequate skills.16

This public-spirited rationale for occupational licensing is known as the Public Interest or Market Failure Theory,17 and as late as the 1970s it was widely perceived to be the primary motivator of policymakers.18 Since then, however, this essentially benevolent view of economic regulation has lost favor in the economic community.19 The reason is that the Public Interest Theory rests upon an unrealistic understanding of the motivations and limitations of government actors and how public policy actually gets made. There is no guarantee that elected or appointed officials are subject matter experts or will select regulatory schemes that will correct market flaws, rather than satisfy the demands of favored constituents. And because statutes are no less difficult to repeal than to pass,20 even blatantly anticompetitive, irrational, or otherwise non-public-spirited laws may stay on the books indefinitely.21

Moreover, the Public Interest Theory mistakenly idealizes the motives of government officials by assuming they reliably act in the public’s best interests despite increasing evidence to the contrary.22 As Yale Law School Professor Peter Schuck has noted, Public Interest Theory stands as a “vacuous and dangerously naive” account of public policymaking, both as to how public policy is adopted and how it is implemented.23 As he puts it, “rational self-interest (as the actor perceives it) unquestionably drives most political behavior most of the time.”24

A notable feature of Public Interest Theory is that it fails to explain a rather curious fact: Private firms often urge governments to adopt restrictive regulatory regimes, including occupational licensing — conduct that is the exact opposite of what Public Interest Theory predicts. Historian Lawrence Friedman found that practice prevalent throughout American history, noting that “the licensing urge flowed from the needs of the licensed occupations. The state did not impose ‘friendly’ licensing; rather, this licensing was actively sought by the regulated.”25

Economist and Nobel laureate George Stigler was the first to explain why that odd scenario is so widespread. He found a simple explanation for companies’ otherwise irrational conduct — namely, incumbent businesses endorse licensing requirements because it protects them against competition.26 Professor Walter Gellhorn summarized that phenomenon as follows:

“The thrust of occupational licensing, like that of the guilds, is toward decreasing competition by restricting access to the profession; toward a definition of occupational prerogatives that will debar others from sharing in them; toward attaching legal consequences to essentially private determinations of what are ethically or economically permissible practices.”27

In short, licensing requirements enable incumbents to receive what economists label “economic rents” — that is, supracompetitive profits made available by laws limiting rivalry. Any benefit that the public receives is largely fortuitous and almost invariably outweighed by its costs.

Stigler was one of the first scholars to subject political behavior to economic analysis and offer a rational economic explanation for irrational political behavior.28 But others followed. In fact, the process of applying microeconomics and game theory to politics gave rise to a new way of analyzing the operation of the two, one known today as Public Choice Theory.29 Public Choice Theory offered a view of market regulation that was materially different from the one that underlies Public Interest Theory. In particular, Public Choice Theory explains why regulated businesses, not consumers, prefer and seek out licensing requirements. Heritage Foundation scholar and co-author Paul Larkin has observed:

Public Choice Theory teaches that elected officials do not fundamentally change their character and abandon the rational, self-interested nature they display as individual participants in a free market when assuming public office. The person that is “an egoistic, rational, utility maximizer” in the market also has that nature in the halls of government . . . . Producers, consumers, and voters seek to maximize their own welfare; politicians, to attain or remain in office; and bureaucrats, to expand their authority. The result is trade in a political market. Interest groups will trade political rents in the form of votes, campaign contributions, paid speaking engagements, book purchases, and get-out-the-vote efforts in return for the economic rents that cartel-creating or reinforcing regulations, such as occupational licensing, can provide. Government officials are aware of interest groups’ motivations and use those groups to their own political advantage. Lobbyists and associations serve as the brokers.30

Public Choice Theory has become an accepted approach to the analysis of political behavior.31

Public Choice Theory recognizes that legislators have complementary strategies. “Rent creation” is the adoption of competitive restrictions, such as occupational licenses, for the benefit of a few incumbents. The licensing requirement generates economic rents for incumbents (supracompetitive profits) and political rents for politicians (campaign contributions, book sales, voter-turnout efforts, etc.). “Rent extraction” is the threat of new legislation that would reduce the rents incumbents receive from an existing scheme.32 Proposed legislation would lower a firm’s profits or increase its costs by eliminating a benefit it presently enjoys (e.g., an occupational licensing requirement that keeps out would-be competitors) or by imposing new regulatory burdens, such as environmental or workplace regulations.

Notably, legislators need not actually get a bill enacted in order to gain political rents. The mere threat to introduce a regulatory bill can often suffice. Known as “cash cows,” such bills have the sole purpose of extracting political rents from interested parties33 and can be used for rent extraction over and over again throughout a legislator’s term in office.34

The point is not that all economic legislation flows from the selfish desires of politicians and influential constituents seeking to advance their own interests at the expense of would-be competitors. Rather, the point is that these motivations are sufficiently powerful — and sufficiently well-documented — that they should significantly inform our understanding of current occupational licensing laws and the urgent need for reform.

In short, licensing requirements enable incumbents to receive what economists label “economic rents” — that is, supracompetitive profits made available by laws limiting rivalry. Any benefit that the public receives is largely fortuitous and almost invariably outweighed by its costs.

III. Variations in Licensing Requirements Undercut Public-Welfare Claims

It is increasingly difficult to justify the patchwork blanket of occupational licensure that covers America. While the intermittent and uneven nature of occupational regulation makes a precise summary difficult, experts estimate that roughly 1,000 occupations require licensing in at least one state.35 And while policymakers in different states will have varying tolerance for risk, uncertainty, and various human and financial costs when it comes to regulating vocations, the sheer magnitude of the variance among states seems suspicious. Simply put, if the public benefits from occupational licensing were obvious (and/or genuine) for any given vocation, we would expect to observe broad consensus in legal and regulatory requirements across the states, both in terms of what occupations are regulated and what credentials are required for licensure.

By contrast, if the impetus for licensing is driven by the desire of existing businesses to shut out competitors, as the discussion of public choice theory in Part II above suggests, then we would expect to observe inconsistent and varying schemes of vocational licensing across the states, both in terms of which occupations are licensed and the credentialing requirements for the same vocations across different states. Thus, if one industry group possessed significant political influence in one state but not another, we could check to see whether that influence appeared to translate into occupational-licensing policies congenial to those groups. Indeed, if licensure is significantly driven by such special-interest dynamics, we could reasonably expect to observe a wide variation in the education and experience requirements that are imposed in different states, since those requirements would be driven by industry groups’ and policymakers’ political needs and desires, not the public interest.

In fact, an examination of the licensing regimes across the 50 states shows notable inconsistency in occupational licensing, both in terms of which jobs are regulated and the credentials required for people doing the same job in different states — precisely what Public Choice Theory would predict. The following sections consider these variations across states and vocations in four different contexts: (1) vocations that are licensed in practically all states; (2) vocations that are licensed in a significant number of states but not all; (3) vocations that are licensed by relatively few states; and (4) the handful of “black swan” vocations that are licensed by just one or two states, such as florists in Louisiana and “forest workers” in Connecticut. What we see in all four cases is a lack of coherent rationale for which occupations are licensed and which ones are not, as well as remarkable discrepancies between the risk or complexity of various occupations and the extent of the training and education required for licensure. This tends to underscore the suggestion from Public Choice Theory that occupational licensing laws are frequently more concerned with advancing private interests than public ones.

A. Differing State Standards for Commonly Licensed Vocations

Our first set of occupations consists of those that are licensed in every state, with only occasional exceptions. These occupations cover the income spectrum, from high-income occupations to ones that generate relatively low pay. Nearly every state licenses health-related occupations such as doctor, nurse, pharmacist, and emergency medical technician, as well as lawyer, accountant, barber, cosmetologist, truck driver, preschool teacher, pesticide applicator, funeral director, school bus driver, and athletic trainer. Over 35 states license makeup artists, security guards, HVAC contractors, and massage therapists.36

As noted in the Executive Summary, while states have licensed physicians, dentists, and lawyers for more than a century, there has been an explosion in occupational licensing over the past 50 years as incumbent firms and trade associations have discovered the competition-stifling benefits (from their perspective) of government regulation and pushed hard for more of it.37

As suggested above, it is telling that even when it comes to universally licensed occupations such as barbers and cosmetologists, there is often a large variance among the states with respect to the experience and training required for licensure. For example, in Maryland a barber needs 280 days of experience or education to obtain a license.38 In Idaho, however, a barber needs 630 days of education or experience.39 Is the hair of an Idahoan really more complex to cut than the hair of a Marylander? And while we would certainly expect to see some variation across states, two-and-a-quarter times as much training is a huge variation; it would be like some states requiring lawyers to spend three years in law school (as all states currently do) with other states requiring seven years — or nine years of medical school when the current standard is four. Seen through that lens, and considering the additional expense and opportunity costs involved for aspiring barbers in Idaho, the variation is astonishing. But it is not unusual — consider several other radical variations in credentialing requirements for low- and moderate-income occupations:

- Ten states require four months or more of training for manicurists, while Iowa requires nine days and Alaska only three.40

- Oregon requires 367 days of education and experience for school bus drivers; New Jersey requires 1,095 days.41

- One can become a licensed cosmetologist in New York or Massachusetts with just 233 days of training and experience, whereas Iowa, Nebraska, and South Dakota require more than double that — 490 days.42

- About two-thirds of the 39 states that license massage therapists require only four months of training while others require twice that amount and Maryland nearly triple, with 11 months.43

Another notable instance of licensing variance is that of internal variance within states — that is, what we see when we compare the requirements of one occupational license with another in the same state. For example, lawyers in Michigan must have the national standard 1,200 hours of classroom education, whereas Michigan barbers must complete 1,800 hours of coursework.44 Or consider New Jersey’s licensure of emergency medical technicians (EMTs), which requires 28 days of experience and education, with its far more stringent requirements for cosmetologist (280 days of training and experience), barber (280 days), and locksmith (1,176 days).45 Thus, for every day of training that it takes to become an EMT in New Jersey, it takes 40 days of training to become a locksmith. But it seems highly unlikely that the body of knowledge a locksmith must master to do his job properly is 40 times greater than what an EMT must know — if anything, it seems the ratio should be reversed. Of course, this does not tell us whether New Jersey’s training requirements are too light for EMTs or too stringent for locksmiths; but it does strongly suggest a lack of consistency and perhaps even rationality in that approach to occupational licensing.

B. Differing State Standards for Vocations Licensed in Some States, But Not All

Our second set of occupations is composed of those for which some states impose licensure requirements, but many other states do not. Thus, for example, between 20 and 35 states license occupations such as milk sampler, auctioneer, midwife, floor sander contractor, animal breeder, taxidermist, school sports coach, optician, and travel guide. Nationally, there is no clear consensus on requiring a license for these occupations, and little if any evidence that consumers in non-licensing states face any greater risk from incompetent or unethical practitioners.

When we look at almost any given occupation in this second set of licensed occupations, we again see notable variance when comparing the burdens of licensure created by state governments. Thus, Florida charges auctioneers $1,000 for a license and requires 19 days of education or experience.46 Hawaii, however, charges would-be auctioneers only $15 and has no education or experience requirement.47 The 19-day education and experience mandate is common in many of the states that license auctioneers, although there are outliers like Kentucky and West Virginia (both of which have 730-day mandates)48 and Tennessee (which has a 756-day mandate).49

As with commonly licensed vocations like EMTs and locksmiths in the preceding section, we again see inexplicable variations in how onerous licensing requirements are for different vocations within the state. Compare Tennessee’s 756-day requirement for auctioneers with the mere four days of training and experience for childcare workers.50 Of course, running an auction is skilled work that involves evaluating goods, working with buyers and sellers, and perfecting sometimes complex financial transactions. But only five states require more than 45 days in education or experience to be a licensed auctioneer, which suggests that Tennessee’s auctioneer requirements are unduly onerous, both as compared to other jurisdictions and as compared to other vocations within the state.

C. Vocations That Are Licensed by Relatively Few States

Our third set of licensed occupations comprises those that are licensed in a relatively small number of states. Again, the absence of any evidence that consumers are harmed in the vast majority of states that do not license these vocations severely undermines any public-interest rationale and strongly suggests that the goal of these licensing schemes is not to protect consumers from harm but state-licensed workers from competition.

Occupations that are licensed in fewer than 20 states include sign language interpreter, chimney sweep, parking valet, farrier, landscape worker, funeral attendant, travel agent, tree trimmer, title examiner, and interior designer.

A report by the Institute for Justice notes that the lack of consistency among states in this category of occupations is striking:

[I]rrationalities are particularly notable when few states license an occupation but do so onerously. One clear example is interior design, the most difficult of the 102 occupations [surveyed] to enter, yet licensed in only three states and D.C. Another is social service assistants, the fourth most difficult occupation to enter. It requires nearly three-and-a-half years of training but is only licensed in six states and D.C. Dietetic technicians must spend 800 days in education and training, making for the eighth most burdensome requirements, but they are licensed in only three states. Home entertainment installers must have about eight months of training on average, but only in three states. The seven states that license tree trimmers require, on average, more than a year of training.51

Would-be tree trimmers in Maryland face an experience-and-education requirement of 1,095 days, but they can work in any of the surrounding states with no license of any kind.52 There appears to be no evidence that trees are trimmed more competently in Maryland than in bordering states, nor any empirical support for requiring Maryland tree trimmers to spend three years acquiring a license that only six other states license at all.53

D. “Black Swan” Licensing of Vocations

The fourth and final set of occupations we consider are those licensed by only one or two states. If we assume that legislators license occupations based on a demonstrable need, then it is difficult to see why licensing of these occupations should occur. The demographics and economies of the 50 states and the District of Columbia are not so different that there is an objective need for licensing of some vocations, but only in one particular area of the country. Nor is it plausible to suppose that legislators in only one or two states have discovered some compelling reason to regulate these vocations that continues to elude legislators in other states.

For example, Louisiana is the only state in the country that licenses florists. A person who takes two flowers and puts them together in an aesthetically appealing way has created an “arrangement,” which can be sold only by a state-licensed florist. The Institute for Justice challenged the law twice, prompting the state to eliminate the hands-on portion of the licensing exam that helped ensure a nearly 65-percent failure rate among applicants. (Louisiana still licenses florists, and applicants must pass a written true-false exam that is far less onerous — and less subjective — than the defunct practical exam.)

Other vocations licensed by just one state include “forest worker” (Connecticut), “conveyor operator” (Connecticut again), and “fire sprinkler tester” (Michigan). Vocations licensed by just two states include “psychiatric aide” (California and Missouri), “nursery worker” (Idaho and Nevada), and “electrical helpers” who assist electricians (Minnesota and Maine).54 As with Louisiana florists, any public harms from the activities of unlicensed nursery or forest workers, fire sprinkler testers, or electrical helpers in other states have yet to be documented empirically.

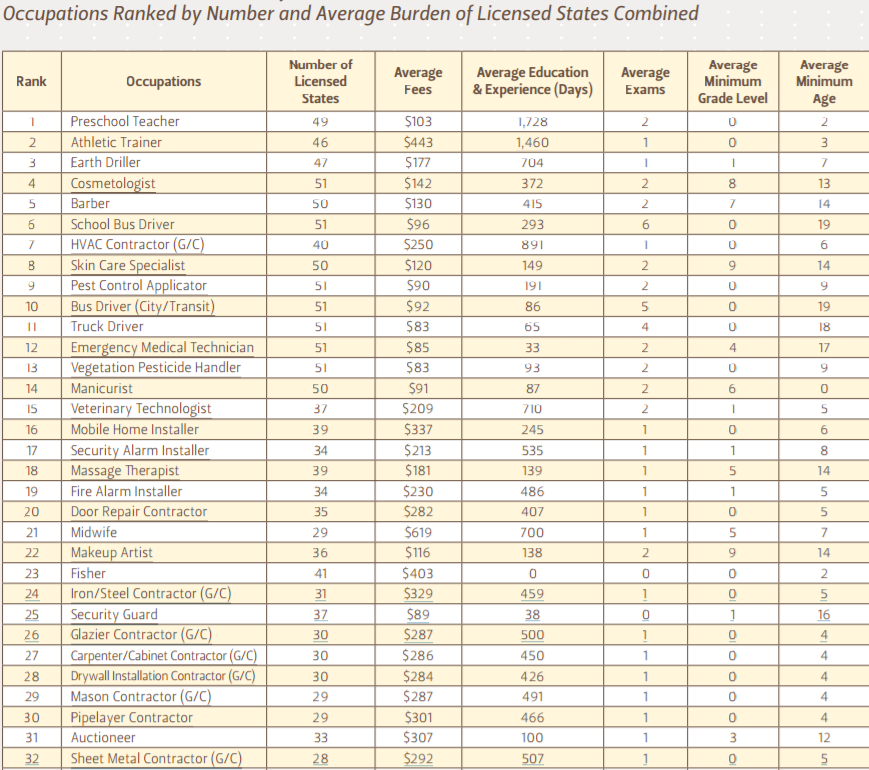

The following table from License to Work helps illustrate the extent to which even relatively harmless and mundane occupations are affected by occupational licensing, as well as the cost of those regulatory burdens both in time and dollars.55

This brief survey of licensure across the nation suggests that the variance in licensure requirements — both across states when the same occupation is compared, and within a given state when different occupations are compared — is often so large as to be arbitrary and unjustifiable.

Indeed, if licensure is significantly driven by such special-interest dynamics, we could reasonably expect to observe a wide variation in the education and experience requirements that are imposed in different states, since those requirements would be driven by industry groups’ and policymakers’ political needs and desires, not the public interest.

IV. The Problem of Licensing Creep

As demonstrated in Part III, states vary wildly in their licensing requirements — both in terms of what occupations are restricted and in how draconian licensing requirements may be for any given profession. But there is another dimension to the problem of “occupational licensing run wild.” As noted in Part II’s discussion of Public Choice Theory, established commercial interests tend to support licensing regimes as a means of protecting against competition from new entrants into the market. Importantly, those same self-interested motives often prompt incumbent firms to lobby for the expansion of existing licensing regimes — a problem we refer to as “licensing creep.”56

The states often differ radically in how they define occupations subject to licensing requirements. For example, a handful of states require licensing for landscapers; however, each state differs in defining exactly what sort of work requires a landscaping license.57 Similar issues are presented across the country in various industries — typically with an incumbent group seeking to exclude competition from non-licensed newcomers (e.g., doctors seeking to restrict what services nurses may offer patients, or urging restrictions on services pharmacists may offer).58

To illustrate the point, consider the ongoing battle in many states over whether someone providing teeth-whitening services should be required to have a dental license. Interestingly, in those states that allow non-licensed service providers to offer teeth-whitening services, consumers can buy over-the-counter teeth-whitening agents, or they may have their teeth whitened by non-licensed service providers, at a significantly lower cost than charged in a dentist’s office.59 But not surprisingly, dentists overwhelmingly take the view that only dentists should be allowed to provide teeth-whitening services. In North Carolina, the state dental board went so far as to send out cease-and-desist letters threatening to initiate legal action against non-dentists offering teeth-whitening services.60 North Carolina’s dental board is comprised predominantly of practicing dentists who had a pecuniary interest in eliminating competition from non-licensed service providers.61 It is common for members of the regulated vocation to be disproportionately represented on the relevant licensing board, and it is questionable whether their greater subject-matter knowledge outweighs the substantial conflict of interest when licensees, in effect, regulate themselves and their colleagues.62

This is one form of what political theorists call “agency capture” — whereby regulated industries effectively co-opt regulatory regimes by placing friends in important governmental roles.63 But once co-opted in this fashion, these licensing boards tend to act not necessarily in the public interest, but in the (often anti-competitive) interest of the profession that they are supposed to regulate.64

Consider the example of California’s Structural Pest Control Board, and the story of Alan Merrifield — owner and operator of Urban Wildlife Management, Inc. At the time he started his business he had no idea that California law required a license for service providers using physical objects, like spikes on windowsills or chimneys, to discourage birds and other animals from taking up residence in buildings or homes.65 He found out the hard way when the Pest Control Board tried shutting him down for practicing pest control without a license, even though he used no poisons, traps, or other techniques normally associated with pest control.

Perhaps the strangest aspect of California’s pest control licensing regime was in its random application.66 Merrifield was required to have a license to install spikes to ward off pigeons; however, no license would be required if those same spikes were installed to keep away seagulls.67 Likewise, Merrifield could install screens to control squirrels, but not mice.68 The explanation for this uneven approach is simple: licensed pest control agents cared a great deal about protecting their monopoly with respect to lucrative pests like rats, mice, and pigeons, and very little about who dealt with other pests like bats, raccoons, and seagulls. Thus, the law was tailored to the economic interests of licensees rather than any genuine public policy concerns.69

Represented by the Pacific Legal Foundation, Merrifield persuaded the Ninth Circuit that there are limits on government’s ability to interfere with people’s livelihoods while catering to the demands of interest groups like state-licensed pest controllers in California.70 Nonetheless, Merrifield also serves as a cautionary tale. Although the court ultimately ruled for Merrifield, the decision makes abundantly clear that California might just as well impose severe pesticide-oriented licensing requirements on non-pesticide service providers, so long as the restrictions are applied across the board to all service providers without arbitrary exceptions.71

California isn’t the only jurisdiction with this sort of licensing creep. Just next door, the Arizona Pest Control Commission threatened three professional landscapers with substantial fines for using over-the-counter herbicides, such as Round-Up, to kill weeds.72 The Commission’s assertion that only licensed pest controllers with 3,000 hours of state-mandated training and experience could apply household herbicides for compensation — when homeowners use the same products without any special training — was insupportable. Faced with a lawsuit, the Arizona legislature moved quickly to create a statutory exemption.73

In 2004, the same Pest Control Commission threatened 17-year-old Christian Alf with fines for charging $30 to find holes in people’s houses and cover them with wire mesh to keep out “roof rats” in Tempe.74 The Commission had taken action after an article on the front page of the Arizona Republic commended Christian on his entrepreneurial spirit and prompted more than 200 phone calls from people eager to pay for his services.75 Nothing in state law prohibited non-licensees from stapling wire mesh over holes in people’s homes, and indeed a Commission-approved guide notes that licensees “should take every opportunity to educate building owners as to the importance of building maintenance and encourage them to seal holes and cracks in doors and windows and around pipes and wiring.”76 But when Christian began making money doing precisely that, he was accused of poaching on turf reserved exclusively for state-licensed pest controllers.

Ultimately, the Pest Control Commission backed down in the face of threatened litigation by the Institute for Justice.77 But not everyone is fortunate enough to receive pro bono legal representation in these sorts of cases, which means that when licensing boards take an aggressive position like this, most individuals feel that they have little choice but to accede to their demands, no matter how unreasonable.78

… established commercial interests tend to support licensing regimes as a means of protecting against competition from new entrants into the market. Importantly, those same self-interested motives often prompt incumbent firms to lobby for the expansion of existing licensing regimes — a problem we refer to as “licensing creep.”56

Receive more great content like this

V. Costs and Benefits of Occupational Licensing

A. Economic Costs

A growing body of economic research indicates that stricter occupational licensing generates a number of economic costs. The first, and most readily apparent, consists of increases in consumer prices. In two widely cited examples — those of nurse practitioners and dental hygienists — marginally more restrictive licensing raises consumer prices by around 3 to 16 percent.79 The logic behind this is straightforward: when entry into a profession is limited, the remaining incumbent workers can charge a premium for their services.

The second type of cost consists of reduced access to employment. Some workers will manage to pay the sizeable but needless cost in time and money of obtaining a license, but others will not. In some cases, workers are categorically barred from receiving a license for reasons that do not withstand scrutiny, as with applicants whose criminal record is irrelevant to the particular profession, but nonetheless constitutes a bar to licensure.

Barriers to entry for workers tend to raise wages for those who successfully obtain a license (whether by paying the upfront costs or being grandfathered into the profession) and lower wages for those who are excluded. Estimates of the wage impact of licensing vary between about 5 and 15 percent, depending on the dataset and the method used to render licensed and unlicensed workers comparable.80 Estimates also differ by occupation, which is unsurprising given that the burden of licensing restrictions varies greatly across occupations.81

Importantly, the workers most harmed by licensure are likely not the same as those who manage to obtain it. For example, tighter licensing restrictions for teachers appear to have reduced the number of Hispanic teachers (incidentally, without raising quality of instruction).82 Similarly, in states that regulate interior design there is evidence that blacks, Hispanics, and older workers seeking to switch careers later in life are disproportionately excluded from the field.83 The same is true of African hair braiding, where there appears to be a direct relationship between the amount of training required (if any) and the number of providers working in the field.84 Thus, workers who would have more difficulty paying the opportunity cost of licensure are simply less likely to successfully navigate the system, reducing their access to ladders of economic opportunity.

Reduced access to employment can take a number of different forms. One is a consequence of the state-based licensure system, combined with a general lack of interstate reciprocity in licensure. When individuals incur considerable costs in time and money to obtain licenses in a particular state, they will be disinclined to duplicate their efforts, even when the market (and consumers) would be better served by their practicing in multiple states. This is most obviously a problem when it comes to interstate migration, which is demonstrably lower for licensed workers relative to comparable workers with certificates and those without licenses.85

B. Impact on Innovation

As the Federal Trade Commission recently noted in a study of the “sharing” economy, “[i]n our competitive economy, innovation is a major driver of long-term consumer welfare gains.”86 But what benefits consumers can threaten existing businesses that may seek to make up for their lack of innovation through the exercise of raw political power. Giving incumbent firms the ability to saddle would be competitors with onerous and often outdated licensing requirements presents a serious threat to innovation across a wide array of vocations, including medicine, law, education, and transportation.87 Of course, the failure of new products, services, or technologies to emerge due to occupational overregulation is impossible to fully document or calculate. That said, both common sense and abundant anecdotal evidence suggest that the effects of “occupational license run wild” on innovation are substantial.

Consider two examples from the medical field. First is the ability to remotely diagnose and treat patients, broadly referred to as “telemedicine.” Whether this means having the x-ray or MRI of a late-night emergency-room patient interpreted immediately by a radiologist in another jurisdiction — perhaps even on the other side of the world where it is the middle of the workday — or enabling a rural patient to be “seen” by a doctor on video instead of driving hundreds of miles for an in-person consultation, telemedicine promises to bring more services more quickly to more people at a lower cost than the traditional in-person model. But not everyone has embraced this innovation, and indeed, the Texas medical board amended its rules to require face-to-face consultation in a transparent attempt to disrupt the business model of Teladoc, Inc.,88 a company whose motto is “[s]peak to a licensed doctor by web, phone, or mobile app in under 10 minutes.”89 Teladoc has challenged that rule change in court, and the case remains pending at the time of this writing.

A particularly poignant example of rigid licensing policies stifling innovation in the medical field is a nonprofit called Remote Area Medical that puts on free medical clinics for low-income people, especially in rural areas. Remote Area Medical (or “RAM”) has been featured in dozens of media outlets, including The New York Times, CNN, and 60 Minutes.90 Despite its extraordinary track record providing desperately needed care to thousands of patients, RAM has experienced significant difficulty staffing its free medical clinics because it depends on volunteer doctors, dentists, nurses, and other health-care providers, many of whom reside outside the state where the clinic is being held and are not licensed in that jurisdiction. Some states, including RAM’s home state of Tennessee, have been quick to accommodate — including passing special legislation to exempt RAM volunteers from applicable licensing requirements — while other states have not.

Law is another field in which hidebound resistance to innovation is both common and costly. Among other things, lawyer-licensing laws help perpetuate the one-size-fits-all approach to legal education that saddles aspiring lawyers with increasingly large student debts while leaving many unequipped for the real-world practice of law. State-by-state licensing also makes it difficult for lawyers to serve businesses and other clients with legal needs in different jurisdictions since most lawyers are licensed in just one state. Meanwhile, ethics rules prohibit lawyers from practicing in firms that are owned by non-lawyers, which does much to shield law firms from competition from, for example, large accounting firms. And perhaps most importantly, the difficulty of defining just what constitutes the “practice of law” has made it difficult for non-lawyer providers, such as Nolo,91 to determine with confidence precisely which services they may provide — such as do-it-yourself wills and business incorporation kits — and which ones remain the exclusive (and often expensive) purview of state-licensed lawyers.92

It is impossible to quantify the cost to society of new products that never come to market, better services that consumers don’t get to enjoy, or the perpetuation of inefficient business models like taxi cabs or telephone monopolies who owe their existence to misguided regulations. But, the cost appears substantial.

C. Human Costs of Licensing

When considering the empirical costs and benefits of particular policies, it can be easy to lose sight of the effect those policies have on the lives of actual people. Below is just a small sample of specific instances in which excessive occupational licensing has negatively impacted workers, entrepreneurs, and consumers.

Sandy Meadows versus the Louisiana Horticulture Commission

As noted above, Louisiana is the only state in the country that licenses florists. And while that may seem comical at first, preventing people whose only vocational skill is creating attractive flower designs from using that ability to support themselves is no laughing matter. Sandy Meadows found that out when agents of the Louisiana Horticulture Commission stopped by the Albertson’s grocery store where she was running the floral department without a license and warned management that unless they hired a state-licensed florist, the store would be fined and prohibited from selling any more floral arrangements. The store only needed one florist and had no choice but to let Sandy go.

It’s not that she didn’t know about the florist licensing or couldn’t be bothered to get a license. On the contrary, Sandy took the licensing exam five times but flunked it every time. Was it because she was just a bad florist who had no business in the trade? Hardly. Instead, the problem was the state’s licensing exam, the practical portion of which required applicants to create four floral arrangements in four hours that would then be judged by a panel of working florists brought in by the state to judge the work of would-be competitors. These private-sector judges were hard on applicants, and the exam had a pass rate of less than 40 percent in the ten years preceding a legal challenge to the law in 2003.

The state defended the law both as a means to protect consumers from substandard floral arrangements and also as a public-safety measure protecting florists and customers alike from the alleged physical dangers of unlicensed floristry. Despite the fact that both concerns are meritless — there has of course been no rash of flower-related injuries for subpar flower arranging in the 49 states that do not license florists — a federal judge upheld Louisiana’s florist licensing law.

As for Sandy Meadows, Louisiana’s florist licensing law is a moot point. Shortly after losing her job managing Albertson’s floral department at the behest of the Louisiana Horticulture Commission, Sandy died alone, unemployed, and in poverty.93

Flytenow versus the Federal Aviation Administration

Innovative technologies that connect service providers directly to consumers are changing the way people live, work, and travel. From Uber and Lyft in the transportation industry to Airbnb in the hospitality industry, people are using the power of technology to connect with one another and trade goods and services in a way that has historically been neither feasible nor cost-effective. In the process, consumers are getting access to desired services at lower costs and pioneering businesses and service providers are reaching markets they would not otherwise. But at the same time, government regulators are applying licensing requirements to shut down some of these new, innovative businesses.

Flytenow, Inc. — a ride-sharing service for the skies — is one of these innovative businesses. Its business model is based on a common and long-standing practice among private pilots — sharing expenses with their passengers to make flights on small aircraft more accessible and cost-effective. Expense-sharing for the cost of flights has been common since the earliest days of aviation, and it has been expressly approved by the FAA. Specifically, under long-standing FAA rules, private pilots and passengers may each pay an equal share of gasoline costs, fees, and other expenses so long as they are traveling to the same location for independent purposes. Pilots would traditionally find passengers by calling or e-mailing friends, relying on word of mouth, or posting flight information on airport bulletin boards.

However, the FAA told Flytenow and its members that private pilots and passengers cannot share expenses if they communicate with one another using the Internet. According to the FAA, sharing expenses by posting a note on an airport bulletin board is permissible, but sharing expenses by posting travel plans on the Internet is not. If private pilots flying four-passenger Cessnas do the latter, they must have the same licensing credentials as pilots of commercial jetliners.

Flytenow pursued a court challenge to the FAA’s crackdown on flight-sharing arranged via the Internet instead of physical bulletin boards. The D.C. Circuit rejected that challenge, and the Supreme Court recently declined to hear the case.

Just as many jurisdictions have sought to do with Uber, Lyft, and other innovative surface transportation options, the FAA has deprived travelers throughout the country of a unique, convenient, and inexpensive travel option by adopting an arbitrary and incongruent licensing scheme.94

Lauren Boice versus the Arizona Board of Cosmetology

Lauren Boice is a cancer survivor who, while undergoing chemotherapy treatment, was unable to leave her house for many basic activities, including cosmetology services. Fortunately, Lauren won her battle with cancer and, like all successful entrepreneurs, saw a demand in the market. So, she opened Angels on Earth. Lauren’s business was to dispatch licensed cosmetologists to customers who were homebound because of immobilizing illnesses.

Even though Lauren did not cut anyone’s hair or do anyone’s makeup, the Arizona Board of Cosmetology told Lauren that she needed a salon license to operate her business. While the Board might have an interest in clean and safe salons, this regulation made no sense because Lauren did not operate a salon — she merely dispatched service providers who were already licensed by the state. In other words, the government’s restriction — requiring Lauren to get a salon license — did not match the government’s purported interest in clean salons because Lauren did not operate a salon.

Fortunately for Lauren, the Board eventually backed down — but only after Lauren waged a 16-month court battle against it with pro bono legal representation by the Goldwater Institute.95

Joba Niang versus the Missouri Board of Cosmetology and Barber Examiners

Natural hair braiding is a beauty practice popular among many African, African-American, and immigrant communities in the United States. Braiding is a very safe practice because braiders do not cut hair or use any dangerous chemicals, dyes, or coloring agents. Yet, in fourteen states braiders cannot legally work unless they become licensed cosmetologists. Missouri is one such state. It requires braiders to take at least 1,500 hours of prescribed training in a licensed cosmetology school and to pass both a written and a practical exam. Cosmetology schools do not teach natural hair braiding, and the licensing examinations do not test it. Missouri thus requires braiders to get a cosmetology license by taking 1,500 hours of instruction — which can cost tens of thousands of dollars — none of which actually teaches how to braid hair.

For Joba Niang, a highly skilled natural hair braider in St. Louis, Missouri’s licensing scheme poses a threat to her business and livelihood. Originally from Senegal, she emigrated from France in 1998 to pursue the American Dream. Growing up, she had learned to braid hair for her family and friends. Upon arriving in St. Louis, she realized that she could use her braiding skills to help support her growing family. For the past 16 years, Joba has successfully operated her own business, providing critical financial stability for her family.

But Missouri’s Cosmetology Board’s enforcement of cosmetology regulations against natural hair braiders has caused Joba to live in constant fear that the Cosmetology Board will shut her business down. She could not afford to spend 1,500 hours and tens of thousands of dollars to comply with Missouri’s cosmetology training requirements, particularly when that training is irrelevant to natural hair braiding.

Along with another natural hair braider, Tameka Stigers, Niang joined with the Institute for Justice to file a lawsuit in federal court arguing that Missouri’s cosmetology laws, as applied to hair braiders, are arbitrary and irrational restrictions that violate their right to earn an honest living under the Due Process, Equal Protection and Privileges or Immunities Clauses of the Constitution. After a loss at the trial court, their case is pending on appeal.

Meanwhile, reform efforts at the state legislature have hit a dead end. Although legislation that would have removed natural hair braiding from cosmetology licensing cleared the House, it never received a vote in the Senate. Dan Alban, the Institute for Justice’s lead attorney on Niang’s and Stigers’ legal case, was told by sources in the state Capitol that “‘money talks in Jefferson City’ and that bills were less likely to be approved if they didn’t have paid lobbyists going office to office to advocate for the bill.”96

Christina Collins versus the Georgia Dental Board

In 2011, Christina Collins had a successful teeth whitening business in Savannah, Georgia. At her retail location, she sold over-the-counter whitening products and instructed her customers on how to apply those products to their own teeth in a clean, comfortable setting. But as her business grew, it attracted attention from the Georgia Dental Board, which accused her of engaging in the unlawful practice of dentistry. The Board told her to shut down her business or face thousands of dollars in fines and years in jail. As a result, Christina closed her business.

Christina was selling the same products that are perfectly legal to purchase in stores and online, and that people use every day at home. Just as people apply those products to their own teeth at home, they did the same at Christina’s business; Christina’s standard practice, as is typically the case with teeth whitening businesses, was to require that customers apply the products to their teeth. Thus, the only difference between a customer applying teeth-whitening products at home and at Christina’s business was the setting in which that application occurred. But it is only the latter that the Georgia Dental Board treats as the unlawful practice of dentistry under the state’s Dental Practice Act.

In 2014, Christina sued the dental board in federal court, alleging that applying the Dental Practice Act to teeth whiteners like hers was unconstitutional because it drew an irrational distinction between customers whitening their teeth at her business and whitening their teeth at home. She alleged that instead of trying to promote public health and safety, the Dental Board was attempting to insulate dentists from competition from teeth whitening business, which charge much less — often 25 per cent less — than what a dentist would charge.

Teeth whitening is a significant source of revenue for dentists. Across the country, dentists push for laws and regulations that shut down their lower-cost teeth-whitening competitors. According to a 2014 report by the Institute for Justice, since 2005, 14 states have changed their laws or regulations to exclude all but licensed dentists, hygienists, or dental assistants from offering teeth-whitening services. And, at least 25 state dental boards have ordered teeth-whitening businesses to shut down.

In Georgia, Christina lost her lawsuit, and her business remains shuttered. Dentists in Georgia have successfully secured government protection of a major revenue source that was threatened by competition.97

D. Lack of Demonstrable Benefits

Occupational licensing stakeholders generally agree — at least in principle — that serious threats to public health and safety are the justification for licensing. Of course, substantial disagreement exists over what constitutes a serious threat to public health and safety, whether the regulatory instrument of licensing is required to address potential threats, and how burdensome licensing requirements must be to ensure health and safety.

Evidence on these considerations will necessarily be somewhat limited. For instance, researchers will typically be unable to evaluate the relative performance of licensing and some hypothetical regulatory intervention, but will be forced to compare actually existing rules that exist across states and time. In particular, when data exists for only a limited range of policy variations, drawing firm conclusions is difficult or impossible.

Take physician licensure, which is now universal throughout the states. It is likely not possible to estimate its contemporary public health and safety benefits, as there is no opportunity to observe comparable places without physician licensure. To the extent that the details of physician licensure vary across time and states, it may be possible to measure the impacts of changes in those details, but this is not informative about the benefits of licensure overall.

From a research perspective, however, it is a strong advantage that licensure in many occupations has been so irregularly implemented across the states. These differences in licensure status facilitate study of the effects of the institution, generating more information than would be available if licensing were a national policy. As documented in Part III above, even for universally licensed occupations, some of the details of implementation are quite important and variation in those details has facilitated valuable research.

What rigorous, systematic evidence do we have on the public health and safety impacts of licensing? A handful of studies have examined these effects, along with quality impacts (i.e., evaluating whether licensed practitioners provide higher-quality services), in occupations ranging from teaching to dentistry. In general, these studies have found no evidence of licensure benefits to service quality, let alone health and safety.

For example, Angrist and Guryan (2007) observed no improvement in teacher quality from more restrictive testing requirements imposed as part of teacher licensure.98 They did, however, estimate increases in wages associated with the more stringent licensure, as would be expected if the stricter rules amounted to a higher barrier to entry. In addition, the number of Hispanic teachers was substantially reduced. In a very different setting, Kleiner and Kudrle (2000) found that stricter dental licensure had no impact on the quality of dental services provided. As with teacher licensure, however, it did raise practitioner wages; additionally, the authors observed increases in the prices faced by patients.99

One area of particular importance is that of scope of practice for medical professionals. States vary in how freely non-physicians and non-dentists are legally permitted to operate; for example, some states allow nurse practitioners to work autonomously and some require them to work under the supervision of a physician. One review100 of the literature that compares patient outcomes for physicians and nurse practitioners found that results were at least as favorable for nurse practitioners, suggesting that incremental loosening of scope of practice restrictions would not cause deterioration in public health.

The Institute for Justice conducted a study of the possible benefits of licensing tour guides, which a number of U.S. tourist destinations do, including New York City, New Orleans, and Charleston, South Carolina. Washington, D.C., also licensed tour guides until 2014, when the law was struck down in federal court,101 thus creating the opportunity for an empirical “before and after” analysis. The study concluded that Washington, D.C.’s licensing regime did nothing to improve the quality of tour guides and served only to raise barriers to entry into the D.C. tour-guide market.102

An Obama White House report on occupational licensure contains additional detail on the relevant studies, only a small number of which find any quality impacts, and none of which imply serious, credible risks to public health and safety from less restrictive occupational licensure.103

Importantly for purposes of this paper, which seeks to challenge not the practice of occupational licensing itself but rather the overzealous mindset we call “occupational licensing run wild,” the available evidence does not support abandoning occupational licensing wholesale, including even the de-licensing of physicians. This is emphasized by a recent study that examined licensing of midwives in the first half of the 20th century. The studies previously mentioned considered incremental policy differences that feature in contemporary discussions of the appropriate degree of licensing. By contrast, Anderson et al. (2016) found that the introduction of medical licensing — in this case, that of midwives — was associated with significant improvements in public health.104

As the study of licensing progresses, researchers will learn more about the quality and safety effects of licensing rules, permitting an even more informed policy discussion. Developing new sources of administrative data on health and other outcomes, combined with a detailed accounting of changes in state licensure restrictions over time, will be critical to achieving this progress.

Thus, workers who would have more difficulty paying the opportunity cost of licensure are simply less likely to successfully navigate the system, reducing their access to ladders of economic opportunity.

VI. Bipartisan Recognition That Occupational Licensing Has Become a Problem

Historically, libertarians and conservatives have been much more concerned than others by the excesses and inadequacies of occupational licensure. Viewed from one perspective this is unsurprising — licensing is one aspect of an overall regulatory regime that right-leaning individuals are likely to view with distrust. To the extent that markets are prevented from making the optimal use of available talent, workers will be both poorer and less free.

But seen from another perspective, it is surprising that left-leaning policymakers and organizations have not been more interested in issues surrounding occupational licensure. Economic theory, as well as a growing body of evidence, suggests that much of the burden of inappropriate licensure falls upon low-income workers and consumers, people with criminal records, and military families. Indeed, some of the clearest empirical findings in the literature have concerned the benefits to high-earning professionals (e.g., dentists105 and physicians106) from restrictive licensing rules that impose costs on lower-earning professionals (e.g., dental hygienists and nurse practitioners). Careful, state-by-state studies of licensing rules by the Institute for Justice,107 the Reason Foundation,108 and others have documented substantial and widely varying burdens even for low-income occupations.

In part because of research like this, people from across the political and ideological spectrum are becoming aware of the costs of excessive and inappropriate occupational licensing. Furthermore, as a result of technological developments, it is no longer a given that occupational licensure is the best way to solve the problem of information asymmetry.

A. Recent Cross-Ideological Engagement

The Obama White House took an approach to licensing reform that surprised many observers. Along with the Treasury Department and Labor Department, it produced a July 2015 report on the issue that struck a critical tone, calling for wide-ranging reforms.109 These included the systematic application of cost-benefit analysis, consideration of less-intrusive regulatory instruments like certification and registration, increased use of public representatives on licensing boards, and enhanced interstate reciprocity, among other suggestions. Following on the report, the White House conducted outreach to state regulators and legislators that aimed at achieving these objectives. Former Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers Jason Furman was particularly vocal about the tendency for licensing rules to reflect so-called rent-seeking by licensed workers.110

This work followed on an earlier report, co-authored by the Obama Treasury and Defense Departments, that examined the challenges licensing often poses for military families. Subsequent outreach conducted by the Joining Forces Initiative was successful in lowering licensing barriers for military veterans whose relevant experience is often ignored by licensing boards, as well as for military spouses who must go through a costly and time-consuming process of re-licensing after each interstate move.111

The Obama Administration was not the only participant in this broader discussion that included those on the left and center of the ideological spectrum. The Hamilton Project, an economic policy group within the Brookings Institution, published a January 2015 policy proposal by Professor Morris Kleiner that has been widely cited in recent years. In the proposal, Kleiner called for some of the same changes advocated for in the White House report, including more emphasis on less-intrusive regulations and enhanced reciprocity.112 Recent empirical research does much to establish the groundwork for reform.

Importantly for the long-run project of understanding the impact of licensing, and in large part due to the work of Kleiner and other researchers, the federal government’s Current Population Survey now includes questions about licenses and certificates.113 Early findings from the survey suggest substantial licensing costs.114

Notably, the licensing reform discussion has also benefited from the criminal justice reform movement. In 2016, the left-leaning National Employment Law Project produced a report that provided detailed information regarding state licensing policies as they pertained to people with criminal records.115 Many states were shown to be permitting irrelevant and unnecessary blanket exclusion of people with records from the licensing system. With so many modern jobs now requiring licensure, these exclusions constitute a serious impediment to successful labor market re-entry.

Along with policy organizations, many activists, scholars, and pundits have also engaged in the larger licensing debate. Many are libertarians or conservatives, like Brink Lindsey of the Cato Institute, who made licensing reform one of the main points of his agenda for enhancing economic growth.116 A number of scholars at the Goldwater Institute,117 Mercatus Center,118 and Institute for Justice119 have written on the topic as well. But while libertarians and conservatives have certainly been prominent in this discussion, progressives have not been absent. Matthew Yglesias120 and Ezra Klein121 of Vox.com, and Dean Baker122 of the Center for Economic and Policy Research have all written about some of the negative effects of misguided licensure requirements. Alan Krueger,123 a former Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers in the Obama Administration, has advocated for a more rational occupational licensing policy.

Policymakers have not been far behind. To take a few recent examples, Arizona’s Governor Doug Ducey and Senators Mike Lee and Ben Sasse have introduced legislation that would rein in excessive occupational licensing requirements.124 Numerous state legislators of both parties have pursued different strategies for reform, and many such efforts are ongoing.125 And the Federal Trade Commission recently created an Economic Liberty Task Force126 that will focus significantly on occupational overregulation, bringing additional publicity to the issue and, where appropriate, potential federal oversight as well.

B. Technology Tackles Information Asymmetry

Most proponents of occupational licensing point to information asymmetry as its primary economic justification. Information asymmetry is the principle that two parties engaging in a transaction do not always have the same information on the quality of the good or service being transacted. The classic example of this is the “lemon”: a used car that appears fine at the time of purchase, but turns out to be defective. For services, an analogous example would be a general contractor installing a deck for your house that looks nice, but collapses in the first storm.

To a degree, this viewpoint was correct for many years. With traditionally little access to objective, third-party data on the true quality of the good or service they were consuming, consumers could often be taken advantage of in a way that could harm not just themselves, but also those around them (think of the downstairs neighbor in the hypothetical deck example mentioned above). This was particularly true for services consumed on an irregular basis, such as locksmith services. In other words, services like these were less likely to have the benefit of a recommendation for a provider from someone in their personal network, particularly when compared to other, typically more frequently consumed services, like house cleaning.

But today, the internet has effectively addressed this information deficit. Now, there are numerous websites and online services that have collected a plethora of reliable data from previous customers about providers in the local services industry. The most immediate impact that this innovation has had is to help quickly weed out low-quality providers. By constantly gathering data on consumer experiences, these websites can alert other potential consumers about unqualified or untrustworthy providers in almost real time. Think of how quickly a customer having a poor experience with a massage therapist could warn other potential clients of the therapist by posting a simple message on a social media channel like Facebook. Similarly, consumers could avoid service providers lacking any positive reviews online. By lowering the cost of disseminating and then incorporating this information, technology companies can effectively warn consumers as to potential “lemons” in a more meaningful way than far more slow-moving licensing review boards.

Digital marketplaces operating in industries traditionally requiring occupational licensing also go a step beyond the state to protect consumers. That is, not only do they provide information that can warn consumers of potentially unfit or untrustworthy service providers, but they also often provide direct downside protection. For example, consumers using Thumbtack to hire a plumber are protected by the company’s guarantee, which will compensate consumers for property damage up to $1 million.127 Likewise, Google Home Services offers a guarantee on some of the providers using their site that will offer consumers their money back if the project is not done to their satisfaction.128 Multiple other marketplaces do the same. This type of downside risk mitigation for consumers is not provided by states, regardless of a provider’s occupational licensing status.

New technologies can also outperform government sanctions of service provider quality by telling consumers more than just that a given provider meets a minimum legal floor of qualifications. While licenses are a simple binary indication that the provider has met the state-specified legal requirements for the occupation, websites that gather data from prior customers and about the provider’s previously completed projects can help consumers distinguish high-quality providers from low-quality ones. For example, you can now find dozens of reviews for your local hair salon on Yelp that will reveal far more about the competency of the stylists working there and their fit for your needs than a document certifying that they have completed a certain number of hours of supervised training.

Imagine choosing a hair stylist for yourself: would you prefer someone with dozens of 5-star reviews and accompanying photos documenting their ability to give someone like you a high-quality haircut or someone with no such reviews but a document confirming their attendance in a state-sanctioned training program? While the latter is no doubt informative that the stylist has some baseline level of competency, there is likely to be far more variance in service quality among those in the latter set than those in the former. Consumers seeking to purchase the stylist providing the best service for their money will no doubt tend to prefer those with the richer set of quality verifications that can be found on Yelp.

Even in the more complex home improvement industry, where the risks and rewards associated with service provider choice are greater, technology companies can still help consumers overcome the information asymmetry problem. For instance, a consumer seeking to hire a general contractor to build a back deck for their home can use a site like Thumbtack to see reviews from previous customers, as well as photos from the projects they have completed.129 With this wealth of information, it is far more likely that the consumer may ultimately choose to work with a contractor that is fit to complete their project as advertised; in other words, they can find a better match than in a system in which the only information provided is that the provider is licensed.

While technology’s main innovation has been to aggregate data from previous consumers, this is far from its only innovation. One clever way of arming potential consumers with information comes from BuildZoom, which surfaces data on the projects licensed contractors have previously completed.130 They do so by scrapping government databases and collecting permit data from municipalities. This gives them data on a variety of dimensions of the projects — such as cost, timing, and scope — that have been previously completed by a contractor; they then show consumers this information in an easy-to-navigate user interface. This enables consumers to know with a high degree of certainty, for example, whether a contractor completed the remodeling project in the next neighborhood over that he or she claimed to do. While that information has always been publicly available, very few consumers had the resources or the bureaucratic understanding to go and pull that data.

Technology companies are also better than the state in incorporating data from reviews and other online sources, saving consumers the trouble of encountering bad service providers. For instance, by regularly completing comprehensive background checks, many online local services directories and marketplaces can remove service providers with alarming criminal histories more expediently than a state licensing review board. Marketplaces can also preemptively deactivate user accounts where troubling reviews build up. This type of ongoing monitoring — which is almost impossible for licensing bodies — ensures that consumers are not entering transactions with an obvious “lemon.”